Crisis Intervention Paper 6h3t2z

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report 3b7i

Overview 3e4r5l

& View Crisis Intervention Paper as PDF for free.

More details w3441

- Words: 4,237

- Pages: 15

Running head: CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

Crisis Management and Intervention Emily James Drake University

Crisis Management and Intervention

1

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

2

When looking at my school’s emergency response procedures, or at least the ones I have available to me in my classroom, I realized that there is not much to them. The flip book of plans and procedures available to teachers and other staff seems like one we stole from another school and slapped our name on. Each response or procedure is very vague and hasn’t been updated for three to four years. As an educator who could experience a crisis at any moment, this is disappointing to me, especially when considering some of the professional development and training Earlham staff underwent in August of 2014. With this being the case, I set up a meeting with Earlham’s Superintendent, who is also the head of our Safety Team, to discuss what changes could be made to Earlham’s district policy regarding a school intruder. Mike Wright, Earlham’s Superintendent, mentioned that in his experience smaller, rural schools error more on the side of being a welcoming community and school than a safe one. He believes this is part of why Earlham’s Safety Committee hasn’t put a strong emphasis on updating their plans (M. Wright, personal communication, 2016). As mentioned above, Earlham has not updated their crisis management policies for three to four years. While the booklet in each classroom was updated in 2013, the more in-depth plans and check lists haven’t been touched since early 2012. According to Everytown for Gun Safety, “schools in the United States have seen almost one school shooting a week since Dec. 15, 2012, when Adam Lanza opened fire at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut” (Christiansen, 2014). With this being the case, I am surprised Earlham has become so slow with updating their policies. However, I am sure we aren’t the only school behind the curve. Additionally, to my knowledge, Earlham does not have anything specific written out about what exact steps to take after a crisis. After watching a great presentation by two of Waukee’s Grief Response Team, I am again disappointed in my district. How could we get

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

3

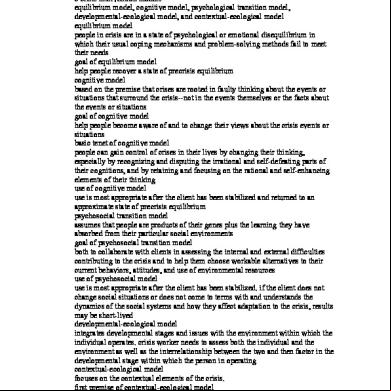

away without yearly updated procedures for an ongoing crisis and not having written steps and procedures for the aftermath of a crisis? In order to help update Earlham’s crisis management and response plans regarding an intruder, I looked at a few different models of crisis intervention that I thought my school could easily adopt. The following resources were reviewed and considered when picking a model of crisis intervention to follow: ● Earlham’s current Intruder/Hostage Lockdown Protocol ● Earlham’s current reunification plans ● The ABC Model of Crisis Intervention (provided in class) ● Waukee’s Grief Response Team Counseling and Building Checklists ● Knox, K. S. & Roberts, A. R. (2005). Crisis Intervention and Crisis Team Models in Schools. 27(2), 93-100. Retrieved from file:///s/emilyjames/Desktop/Crisis %20Book.pdf ● Virginia Department of Education (2002). School crisis management plan. Retrieved from http://www.doe.virginia.gov//safety_crisis_management/emergency_crisis_manag ement/model_plan.pdf ● Roberts, A. R. & Ottens, A. J. (2005). Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 5(4):329-339; doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi030 Model of Crisis Intervention Unfortunately, “we live in an era in which crisis-inducing events and acute crisis episodes are prevalent. Each year, millions of people are confronted with crisis-inducing events that they cannot resolve on their own” (Roberts, 2005). With this being the case, people in crisis turn to many different outlets for , including, “community mental health centers, psychiatric screening units, outpatient clinics, hospital emergency rooms, college counseling centers, family counseling agencies, and domestic violence programs” (Roberts, 2005). Although not mentioned by Roberts, schools can also serve as a place of both during and after a crisis or traumatic event. Therefore, one of the models of crisis intervention that I like most for schools happens to be created by Roberts.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

4

Roberts seven-step crisis model is widely known and has been cited in multiple texts. It is a solution-focused model that incorporates fully understanding the client’s crisis and building rapport with the client in order to move forward and address the issue at hand. Roberts crisis plan has been implemented in a variety of settings and can easily be adapted for schools. Below you will find the a synopsis of each of the seven steps. Step 1: Psychosocial and Lethality Assessment During the first step of Roberts’ model, clinicians must complete a full psychosocial and lethality assessment in order to see if the client has either attempted or contemplated suicide, along with any danger to self or another individual. Additionally, the assessment should, “cover the client's environmental s and stressors, medical needs and medications, current use of drugs and alcohol, and internal and external coping methods and resources” at minimum (Eaton & Ertl, 2000). During this step, Roberts also encourages clinicians and crisis workers to remain sensitive during the interview process, rather than berating clients with questions to receive answers. In doing so, the client’s reactions to the crisis can be assessed and crucial information willingly unfolds through a story versus a question and answer session (Roberts & Ottens, 2005). Step 2: Readily Establish Rapport As a teacher and future school counselor, I have heard many times how important it is to build rapport with students. Not only does forming relationships with students foster a better school environment, it also allows students to feel important and boost self-esteem. Roberts (2005) second step of his crisis intervention model speaks of just this. He asks crisis workers to be genuineness, show respect, and acceptance of their client(s). In doing so, the counselor can and will instill trust and confidence in the client, which will allow all parties involved to get to the root of the problem.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

5

Step 3: Identify the major problems, including crisis precipitants As Roberts and Ottens (2005) point out, “crisis intervention focuses on the client's current problems, which are often the ones that precipitated the crisis.” Therefore, counselors should [inquire] about the [client’s] precipitating event (the proverbial "last straw")”, while also “prioritizing problems in of which to work on first, a concept referred to as "looking for leverage" (Egan, 2002). In doing so, the counselor will be able to better understand how the events escalated to the point of a crisis for the client (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). This understanding is crucial in order to connect with and assist the client in resolving their crisis. Step 4: Dealing with feelings and emotions This stage of Roberts model requires the counselor or crisis worker to be an active participant in order to allow the client to express their feelings and to vent about the crisis they are currently or recently experienced. To complete this step, counseling skills, such as paraphrasing, reflecting feelings, and probing are used during the counseling session (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). Eventually after actively listening to the client, the counselor must will challenge the client’s responses to help “loosen clients' maladaptive beliefs and to consider other behavioral options” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005).

Step 5: Generate and explore alternatives In order to successfully navigate and complete step five, the client and counselor must have previously worked through the client’s deep feelings to establish a baseline of emotional balance for the client. After doing so, the counselor and client can then begin discussing alternatives to the crisis. This conversation can include anything from a no-suicide contract to

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

6

discussing the pros and cons of various programs the client could enter into or sign up for (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). However, Roberts (2005) notes that it is important to discover alternatives with a client in a collaborative fashion, so that the options discussed aren’t solely laying on the client’s shoulders. Alternative choices are usually more successful when done together and are solution-oriented (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). Step 6: Restoring functioning & Implementing and Action Plan This stage seeks to accomplish exactly what it’s title says. Together, the client and counselor work to restore the client to their “normal” and make an action plan that will allow the client to do so. Here, “strategies become integrated into an empowering treatment plan or coordinated intervention” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). The counselor also helps their client to work through the meaning of the precipitated events and crisis. This part of the step if crucial in order for the client to gain “mastery over the situation and for being able to cope with similar situations in the future” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). Step 7: Follow-up Last, but not least step seven includes making a plan for “follow-up with the client after the initial intervention to ensure that the crisis is on its way to being resolved and to evaluate the post-crisis status of the client” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). These follow-up or booster sessions can be provided to the client on a projected schedule, or even on an as needed basis. Regardless, it is important for the counselor to complete check-ins so that clients know they are continually ed and have the tools they need to keep going. Setting and Population that May Experience a Crisis

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

7

As discussed at the beginning of my paper, the setting I have chosen to focus on is a school. While Roberts’ seven step crisis intervention model does not exactly specify how it relates to schools, I believe that it can be easily adapted for educational settings. In the past, schools have been easy targets for various forms of unexpected crises or disaster. With this being the case, crises or traumatic events that take place at schools impact a large arena of people. Students, staff, families, extended families, and even other community feel the effects of a school-wide crisis, especially if the crisis is an active intruder. Not only is an intruder a traumatic event, but it can have after effects that last a lifetime for some individuals. In addition to students, staff, families, and community who might be affected by a school tragedy, service providers, professionals, and other responders may also be impacted. In the case of an active shooter/intruder, schools have always called in external help to manage the situation. Service providers and professionals, like outside mental health counselors, are needed to help assess the trauma caused by such events. In this situation, Roberts’ model of crisis intervention could be used. Other first responders, like EMT’s and police, will also be called in when dealing with an active shooter. Hopefully, if these first responders do their jobs well, the situation will not be as bad as it could had they not been called. However, regardless of who is impacted by such a crisis, it is imperative that all parties band together in order to restore equilibrium and balance in the community. Professionals and service providers may have to reach out to first responders and others after attending to students, staff, and other community to make sure that the event they witnessed does not negatively impact them as well. Should such a situation take place, school counselors and other mental health professionals need to do damage control, in which they assess the degree of trauma inflicted by the situation and what interventions to begin applying. Here, Roberts model of crisis intervention

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

8

can again be applied to help counselors know exactly what to do. If a school has their own postcrisis plan, counselors can use that as well. During this part of the crisis, counselors and professionals should screen those impacted for suicide risk and other self-harm factors. They can do so by following their school/district policy, or other resources provided by any mental health agencies called in to assess the situation. If the crisis is indeed a school shooter, professionals and counselors will have their work cut out for them regarding managing suicide risk, as it can be hard to diagnose and evaluate those impacted in a timely manner. This part of the post-crisis plan is also on-going, as sometimes students and others may experience survivor’s guilt. Anniversaries of the crisis or death may also produce challenges for counselors and professionals when assessing the impact of trauma on individuals. Crisis Versus Non-Crisis Event According to wroldometers.com (2016), there are over 7.4 billion people on this Earth. Despite not having much scientific credibility, I am confident in saying that not a single one of those 7.4 billion people are exactly 100% the same. With this being the case, we cannot make a chart or list for exactly how people will react to a certain situation. There is no right or wrong answer when it comes to a person’s interpretation of a life altering event, such as a crisis. What I deem as a traumatic event or crisis situation, another person may not. For example, to me, a car crash of any kind is traumatic, especially when injuries are involved. However, to an Emergency Medical Technician or service worker, a car crash with multiple injuries and a lot of blood might not be as traumatic, as seeing these kinds of situations is part of their daily job. Therefore, there are differences in diagnosis and counseling interventions when dealing with a crisis or emergency situation. What makes a situation a crisis is how the client reacts to it, not the event itself. Needless to say, counselors must have multiple ideas for how to handle a situation when one

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

9

person deems it a crisis and another does not. Having checklists of what to do will help counselors, but it won’t provide them with all the answers. Role of School Officials During Crisis Management and Intervention Allen et al (2002) states that, “school crises bring chaos that undermines the safety and stability of the school and may make it difficult to protect students and staff. Furthermore, crises put individuals in a state of ‘psychological disequilibrium’ with feelings of anxiety, helplessness, and confusion.” Therefore, during crisis management and intervention school officials must wear multiple hats, especially if located in a small district. According to the American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA) position statement, “the professional school counselor’s primary role is to facilitate planning, coordinate response to and advocate for the emotional needs of all persons affected by the crisis/critical incident by providing direct counseling service during and after the incident” (2007, para. 5). In addition to this statement, schools often times expect their counselors to automatically assume a leadership role before, during, and after a crisis. At my small school, this is the exact case. When our most recent counselor was hired, she was told exactly what committees she was required to serve on, one of which is the school’s Safety Committee. Paralleling these ideas is a study about educators’ perceptions of the role school counselors and psychologists play in schools found that “32% of the teachers and 30% of s believed that the school counselor should assume leadership in the event of a school crisis” (Studer, Baker, & Camp, 2009). After listening to two member’s of Waukee’s grief response team, I am not surprised by the results of Studer, Baker, and Camp’s study. As a consequence of these expectations, Wiger and Harowski (2003) revealed that “when a crisis

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

10

impacted schools, many school counselors assumed istrative roles that resulted in making numerous decisions that were beyond their scope of training and job description.” Regardless, of what a school counselor’s role is in the before, during, and after stages of a crisis, their number one responsibility is to put students first, to assess the traumatic impact of a crisis at hand, and to help figure out a plan of what to do next. With this being the case, I like one of the Counseling Team Leader Checklist Waukee provided us in class. Their checklist spells out specific things that counselors and other of their team need to complete post-crisis. These things include helping to prepare and make a statement with building principals, brief office personnel on parent inquiries, and overseeing that all students are receiving counseling, along with many more steps. In conclusion, of all the research I have gone through, it is obvious that a counselor must assume many roles when managing a school crisis or traumatic event. Structure and Operation of the Emergency Management Plan As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, I met with my school’s superintendent in order to inquire about our crisis management and response systems and interventions we already have in place. While I was disappointed to see that what we have is outdated, I was happy to see that we at least had something. Something is more than nothing in a crisis situation. Currently, Earlham’s protocol for a school intruder/hostage situation includes the following steps: ● The announcement will be given over the intercom ● The teacher will quickly, calmly and immediately lock the door into his/her room and turn the classroom lights off. ● If a substitute teacher is in the building, the classroom teacher closest to the classroom with the substitute should assist the substitute in moving students to the nearest classroom where the students can be locked in. ● If students are out at recess or outside for a classroom activity, proceed to an alternative shelter site that would be used for evacuation (Church of Christ, Methodist Church, Earlham Community Building).

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

11

● The teacher will move students away from doors and glass areas. Close blinds or curtains if possible ● If students are in the Commons area, they need to proceed to the practice gym. ● Take attendance and report by phone, all uned students to the superintendent’s office immediately. Continue to call until you speak to them. Please do not leave a message. If the phone is not available, use email to report students uned for to the superintendent. ● Students will turn desks on sides and use them as a barricade if necessary. ● Do not use the phones or cell phones unless you are reporting uned for students to the office, please. Do not jam our phone lines. ● Office personnel and custodians will lock the academic wing doors, stairwell doors, elevator and office doors for drills only. The will also check the rest rooms. ○ Go to designated safe area within your classrooms immediately. ○ Should have access to a telephone and a computer system, if possible. ○ Phone calls need to be brief. Do not give out information until verified by the building principal or law enforcement. ● All personnel need to wait for further instructions on how to proceed from this point. As of now, this plan has not been needed at Earlham. However, that doesn’t mean we should not keep it updated considering how many mass shootings take place in the United States. In order to update this plan, I would include options for teachers to use their discretion. Two years ago, all Earlham Staff underwent ALICE (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate) training with a few of Iowa’s State Troopers. This training prepares individuals to handle the threat of an Active Shooter, and teaches individuals to participate in their own survival, while leading others to safety (ALICE Training Institute, 2016). ALICE allows teachers and students options including fighting back and fleeing, whereas traditional active shooter/intruder policies ask students, teachers, and other school staff to do exactly what Earlham’s current policy states, lock up and wait. In addition to updating Earlham’s policy with ALICE, I would include something about monitoring students use of cell phones. While it is important for students to be able to reach their parents, this can sometimes cause problems for schools, especially if an intruder is active in a

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

12

school. Parents could show up at the school, alert the media, and cause more harm than good, despite having good intentions. Along with updating a current policy, Earlham also does not have any plans spelled out for exactly what to do the day or two after a crisis, a week after, or even a month after. I think we should have guidelines to follow in case a situation does happen in Earlham and could learn something from other school districts such as Waukee and Southeast Polk, whom have experienced multiple tragedies and crises. Regardless, my superintendent has been “called out” due to my interest in school crisis intervention and management, so I’m hoping changes will take place this summer that will bring our procedures up to date. Collaboration Concerning Crisis Management and Intervention Finally, when speaking of crisis management and intervention, you cannot leave out some of the crucial people involved. As mentioned briefly before, school staff, students, and community are not the only ones impacted by crises. Collaboration is needed across the board in order for a school crisis to be handled properly. This means that when planning or prepping for a possible event, schools should think about what community can help them both during and after a crisis. This includes looking to other school districts and outside agencies for help concerning the mental health needs of students and staff, how to emergency responders, and so on. crisis. As mentioned in their presentation, the Waukee Grief Response Team knows exactly who to call and communicate with after a death. Instead of confining themselves to the services within their district, they reach out to other counselors, mental health providers, and other professionals in order to help assess the impact of trauma on their school. Agencies to for services could include mental health providers that the district already works with, like Orchard

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

13

Place, the local Area Education Agency, or other organizations such as Youth Emergency Services and Shelters, Amanda the Panda, and so on. For Earlham in an active shooter situation, this would mean ing the Earlham police department, as well as the volunteer fire department, and even state troopers since we are a small community. After the event, we would need to call in multiple school and mental health counselors to provide services to our students. We may also need to depend on community and restaurants to help provide food to families in suffering or for staff the day after the event. Additionally, after the event has ed, students still may need referred to outside services, so keeping in with those that help is crucial. Finally, in preparing for such a crisis, Earlham has to reach out to the broader Des Moines community in order to fully update our crises policies and procedures. We are a small school district with limited resources, which means we cannot handle certain situations on our own. Thankfully, I believe we live in a state and broader community that is willing to step in without being asked when needed. When you look at some of the tragedies other schools have faced in Des Moines, you note everyone that has come to help, even in the smallest ways possible. In conclusion, one of my favorite quotes by Fred Rogers seems fitting here. It reads, “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, "Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” Collaboration during a crisis is key, for without it all people involved would crumble.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

14

References ALICE Training Institute (2016). The 1st Active Shooter Response Program. Retrieved from http://www.alicetraining.com/ Allen, M., Burt, K., Bryan, E., Carter, D., Orsi, R., & Durkan, L. (2002). School counselors’ preparation for and participation in crisis intervention. Professional School Counseling, 6, 96-102 American School Counselor Association (2007). Position Statement: Crisis/critical incident response in the schools. Alexandria, VA: Author. Christiansen, A. (2014) Nearly 100 more school shootings since Sandy Hook, report says. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/nearly-100-school-shootingssince-sandy-hook-report-says/ Egan, G. (2002). The skilled helper (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

15

Eaton, Y., & Ertl, B. (2000). The comprehensive crisis intervention model of Community Integration, Inc. Crisis Services. In A. R. Roberts (Ed.), Crisis intervention handbook: Assessment, treatment, and research(2nd ed., pp. 373–387). New York: Oxford University Press. International Association of Chiefs of Police (n.d.) Guide for preventing and responding to school violence. Retrieved from http://www.theia.org/portals/0/pdfs/schoolviolence2.pdf Knox, K. S. & Roberts, A. R. (2005). Crisis Intervention and Crisis Team Models in Schools. 27(2), 93-100. Roberts, A. R. (2005). Bridging the past and present to the future of crisis intervention and crisis management. In A. R. Roberts (Ed.), Crisis intervention handbook: Assessment, treatment, and research(3rd ed., pp. 3–34). New York: Oxford University Press. Roberts, A. R. & Ottens, A. J. (2005). Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 5(4):329-339; doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi030

Stephan, S. H. & Lever, N. (n.d.) Resources for dealing with traumatic events in schools. Retrieved from http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.sswaa.org/resource/resmgr/imported/ListofTraumaResour ces.pdf Studer, J. R., Baker, C., & Camp, E. (2009). The perceptions of the roles of professional school counselors and school psychologists as perceived by educators. Manuscript submitted for publication. Studer, J. R. & Salter, S. E. (2010). The Role of the School Counselor in Crisis Planning and Intervention. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/resources/library/vistas/2010-VOnline/Article_92.pdf Wiger, D. E. & Harowski, K. J. (2003). Essentials of crisis counseling and intervention. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Worldometers.com (20016). Current world population. Retireved from http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/

Crisis Management and Intervention Emily James Drake University

Crisis Management and Intervention

1

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

2

When looking at my school’s emergency response procedures, or at least the ones I have available to me in my classroom, I realized that there is not much to them. The flip book of plans and procedures available to teachers and other staff seems like one we stole from another school and slapped our name on. Each response or procedure is very vague and hasn’t been updated for three to four years. As an educator who could experience a crisis at any moment, this is disappointing to me, especially when considering some of the professional development and training Earlham staff underwent in August of 2014. With this being the case, I set up a meeting with Earlham’s Superintendent, who is also the head of our Safety Team, to discuss what changes could be made to Earlham’s district policy regarding a school intruder. Mike Wright, Earlham’s Superintendent, mentioned that in his experience smaller, rural schools error more on the side of being a welcoming community and school than a safe one. He believes this is part of why Earlham’s Safety Committee hasn’t put a strong emphasis on updating their plans (M. Wright, personal communication, 2016). As mentioned above, Earlham has not updated their crisis management policies for three to four years. While the booklet in each classroom was updated in 2013, the more in-depth plans and check lists haven’t been touched since early 2012. According to Everytown for Gun Safety, “schools in the United States have seen almost one school shooting a week since Dec. 15, 2012, when Adam Lanza opened fire at Sandy Hook Elementary in Newtown, Connecticut” (Christiansen, 2014). With this being the case, I am surprised Earlham has become so slow with updating their policies. However, I am sure we aren’t the only school behind the curve. Additionally, to my knowledge, Earlham does not have anything specific written out about what exact steps to take after a crisis. After watching a great presentation by two of Waukee’s Grief Response Team, I am again disappointed in my district. How could we get

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

3

away without yearly updated procedures for an ongoing crisis and not having written steps and procedures for the aftermath of a crisis? In order to help update Earlham’s crisis management and response plans regarding an intruder, I looked at a few different models of crisis intervention that I thought my school could easily adopt. The following resources were reviewed and considered when picking a model of crisis intervention to follow: ● Earlham’s current Intruder/Hostage Lockdown Protocol ● Earlham’s current reunification plans ● The ABC Model of Crisis Intervention (provided in class) ● Waukee’s Grief Response Team Counseling and Building Checklists ● Knox, K. S. & Roberts, A. R. (2005). Crisis Intervention and Crisis Team Models in Schools. 27(2), 93-100. Retrieved from file:///s/emilyjames/Desktop/Crisis %20Book.pdf ● Virginia Department of Education (2002). School crisis management plan. Retrieved from http://www.doe.virginia.gov//safety_crisis_management/emergency_crisis_manag ement/model_plan.pdf ● Roberts, A. R. & Ottens, A. J. (2005). Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 5(4):329-339; doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi030 Model of Crisis Intervention Unfortunately, “we live in an era in which crisis-inducing events and acute crisis episodes are prevalent. Each year, millions of people are confronted with crisis-inducing events that they cannot resolve on their own” (Roberts, 2005). With this being the case, people in crisis turn to many different outlets for , including, “community mental health centers, psychiatric screening units, outpatient clinics, hospital emergency rooms, college counseling centers, family counseling agencies, and domestic violence programs” (Roberts, 2005). Although not mentioned by Roberts, schools can also serve as a place of both during and after a crisis or traumatic event. Therefore, one of the models of crisis intervention that I like most for schools happens to be created by Roberts.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

4

Roberts seven-step crisis model is widely known and has been cited in multiple texts. It is a solution-focused model that incorporates fully understanding the client’s crisis and building rapport with the client in order to move forward and address the issue at hand. Roberts crisis plan has been implemented in a variety of settings and can easily be adapted for schools. Below you will find the a synopsis of each of the seven steps. Step 1: Psychosocial and Lethality Assessment During the first step of Roberts’ model, clinicians must complete a full psychosocial and lethality assessment in order to see if the client has either attempted or contemplated suicide, along with any danger to self or another individual. Additionally, the assessment should, “cover the client's environmental s and stressors, medical needs and medications, current use of drugs and alcohol, and internal and external coping methods and resources” at minimum (Eaton & Ertl, 2000). During this step, Roberts also encourages clinicians and crisis workers to remain sensitive during the interview process, rather than berating clients with questions to receive answers. In doing so, the client’s reactions to the crisis can be assessed and crucial information willingly unfolds through a story versus a question and answer session (Roberts & Ottens, 2005). Step 2: Readily Establish Rapport As a teacher and future school counselor, I have heard many times how important it is to build rapport with students. Not only does forming relationships with students foster a better school environment, it also allows students to feel important and boost self-esteem. Roberts (2005) second step of his crisis intervention model speaks of just this. He asks crisis workers to be genuineness, show respect, and acceptance of their client(s). In doing so, the counselor can and will instill trust and confidence in the client, which will allow all parties involved to get to the root of the problem.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

5

Step 3: Identify the major problems, including crisis precipitants As Roberts and Ottens (2005) point out, “crisis intervention focuses on the client's current problems, which are often the ones that precipitated the crisis.” Therefore, counselors should [inquire] about the [client’s] precipitating event (the proverbial "last straw")”, while also “prioritizing problems in of which to work on first, a concept referred to as "looking for leverage" (Egan, 2002). In doing so, the counselor will be able to better understand how the events escalated to the point of a crisis for the client (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). This understanding is crucial in order to connect with and assist the client in resolving their crisis. Step 4: Dealing with feelings and emotions This stage of Roberts model requires the counselor or crisis worker to be an active participant in order to allow the client to express their feelings and to vent about the crisis they are currently or recently experienced. To complete this step, counseling skills, such as paraphrasing, reflecting feelings, and probing are used during the counseling session (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). Eventually after actively listening to the client, the counselor must will challenge the client’s responses to help “loosen clients' maladaptive beliefs and to consider other behavioral options” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005).

Step 5: Generate and explore alternatives In order to successfully navigate and complete step five, the client and counselor must have previously worked through the client’s deep feelings to establish a baseline of emotional balance for the client. After doing so, the counselor and client can then begin discussing alternatives to the crisis. This conversation can include anything from a no-suicide contract to

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

6

discussing the pros and cons of various programs the client could enter into or sign up for (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). However, Roberts (2005) notes that it is important to discover alternatives with a client in a collaborative fashion, so that the options discussed aren’t solely laying on the client’s shoulders. Alternative choices are usually more successful when done together and are solution-oriented (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). Step 6: Restoring functioning & Implementing and Action Plan This stage seeks to accomplish exactly what it’s title says. Together, the client and counselor work to restore the client to their “normal” and make an action plan that will allow the client to do so. Here, “strategies become integrated into an empowering treatment plan or coordinated intervention” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). The counselor also helps their client to work through the meaning of the precipitated events and crisis. This part of the step if crucial in order for the client to gain “mastery over the situation and for being able to cope with similar situations in the future” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). Step 7: Follow-up Last, but not least step seven includes making a plan for “follow-up with the client after the initial intervention to ensure that the crisis is on its way to being resolved and to evaluate the post-crisis status of the client” (Roberts and Ottens, 2005). These follow-up or booster sessions can be provided to the client on a projected schedule, or even on an as needed basis. Regardless, it is important for the counselor to complete check-ins so that clients know they are continually ed and have the tools they need to keep going. Setting and Population that May Experience a Crisis

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

7

As discussed at the beginning of my paper, the setting I have chosen to focus on is a school. While Roberts’ seven step crisis intervention model does not exactly specify how it relates to schools, I believe that it can be easily adapted for educational settings. In the past, schools have been easy targets for various forms of unexpected crises or disaster. With this being the case, crises or traumatic events that take place at schools impact a large arena of people. Students, staff, families, extended families, and even other community feel the effects of a school-wide crisis, especially if the crisis is an active intruder. Not only is an intruder a traumatic event, but it can have after effects that last a lifetime for some individuals. In addition to students, staff, families, and community who might be affected by a school tragedy, service providers, professionals, and other responders may also be impacted. In the case of an active shooter/intruder, schools have always called in external help to manage the situation. Service providers and professionals, like outside mental health counselors, are needed to help assess the trauma caused by such events. In this situation, Roberts’ model of crisis intervention could be used. Other first responders, like EMT’s and police, will also be called in when dealing with an active shooter. Hopefully, if these first responders do their jobs well, the situation will not be as bad as it could had they not been called. However, regardless of who is impacted by such a crisis, it is imperative that all parties band together in order to restore equilibrium and balance in the community. Professionals and service providers may have to reach out to first responders and others after attending to students, staff, and other community to make sure that the event they witnessed does not negatively impact them as well. Should such a situation take place, school counselors and other mental health professionals need to do damage control, in which they assess the degree of trauma inflicted by the situation and what interventions to begin applying. Here, Roberts model of crisis intervention

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

8

can again be applied to help counselors know exactly what to do. If a school has their own postcrisis plan, counselors can use that as well. During this part of the crisis, counselors and professionals should screen those impacted for suicide risk and other self-harm factors. They can do so by following their school/district policy, or other resources provided by any mental health agencies called in to assess the situation. If the crisis is indeed a school shooter, professionals and counselors will have their work cut out for them regarding managing suicide risk, as it can be hard to diagnose and evaluate those impacted in a timely manner. This part of the post-crisis plan is also on-going, as sometimes students and others may experience survivor’s guilt. Anniversaries of the crisis or death may also produce challenges for counselors and professionals when assessing the impact of trauma on individuals. Crisis Versus Non-Crisis Event According to wroldometers.com (2016), there are over 7.4 billion people on this Earth. Despite not having much scientific credibility, I am confident in saying that not a single one of those 7.4 billion people are exactly 100% the same. With this being the case, we cannot make a chart or list for exactly how people will react to a certain situation. There is no right or wrong answer when it comes to a person’s interpretation of a life altering event, such as a crisis. What I deem as a traumatic event or crisis situation, another person may not. For example, to me, a car crash of any kind is traumatic, especially when injuries are involved. However, to an Emergency Medical Technician or service worker, a car crash with multiple injuries and a lot of blood might not be as traumatic, as seeing these kinds of situations is part of their daily job. Therefore, there are differences in diagnosis and counseling interventions when dealing with a crisis or emergency situation. What makes a situation a crisis is how the client reacts to it, not the event itself. Needless to say, counselors must have multiple ideas for how to handle a situation when one

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

9

person deems it a crisis and another does not. Having checklists of what to do will help counselors, but it won’t provide them with all the answers. Role of School Officials During Crisis Management and Intervention Allen et al (2002) states that, “school crises bring chaos that undermines the safety and stability of the school and may make it difficult to protect students and staff. Furthermore, crises put individuals in a state of ‘psychological disequilibrium’ with feelings of anxiety, helplessness, and confusion.” Therefore, during crisis management and intervention school officials must wear multiple hats, especially if located in a small district. According to the American School Counselor Association’s (ASCA) position statement, “the professional school counselor’s primary role is to facilitate planning, coordinate response to and advocate for the emotional needs of all persons affected by the crisis/critical incident by providing direct counseling service during and after the incident” (2007, para. 5). In addition to this statement, schools often times expect their counselors to automatically assume a leadership role before, during, and after a crisis. At my small school, this is the exact case. When our most recent counselor was hired, she was told exactly what committees she was required to serve on, one of which is the school’s Safety Committee. Paralleling these ideas is a study about educators’ perceptions of the role school counselors and psychologists play in schools found that “32% of the teachers and 30% of s believed that the school counselor should assume leadership in the event of a school crisis” (Studer, Baker, & Camp, 2009). After listening to two member’s of Waukee’s grief response team, I am not surprised by the results of Studer, Baker, and Camp’s study. As a consequence of these expectations, Wiger and Harowski (2003) revealed that “when a crisis

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

10

impacted schools, many school counselors assumed istrative roles that resulted in making numerous decisions that were beyond their scope of training and job description.” Regardless, of what a school counselor’s role is in the before, during, and after stages of a crisis, their number one responsibility is to put students first, to assess the traumatic impact of a crisis at hand, and to help figure out a plan of what to do next. With this being the case, I like one of the Counseling Team Leader Checklist Waukee provided us in class. Their checklist spells out specific things that counselors and other of their team need to complete post-crisis. These things include helping to prepare and make a statement with building principals, brief office personnel on parent inquiries, and overseeing that all students are receiving counseling, along with many more steps. In conclusion, of all the research I have gone through, it is obvious that a counselor must assume many roles when managing a school crisis or traumatic event. Structure and Operation of the Emergency Management Plan As mentioned at the beginning of this paper, I met with my school’s superintendent in order to inquire about our crisis management and response systems and interventions we already have in place. While I was disappointed to see that what we have is outdated, I was happy to see that we at least had something. Something is more than nothing in a crisis situation. Currently, Earlham’s protocol for a school intruder/hostage situation includes the following steps: ● The announcement will be given over the intercom ● The teacher will quickly, calmly and immediately lock the door into his/her room and turn the classroom lights off. ● If a substitute teacher is in the building, the classroom teacher closest to the classroom with the substitute should assist the substitute in moving students to the nearest classroom where the students can be locked in. ● If students are out at recess or outside for a classroom activity, proceed to an alternative shelter site that would be used for evacuation (Church of Christ, Methodist Church, Earlham Community Building).

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

11

● The teacher will move students away from doors and glass areas. Close blinds or curtains if possible ● If students are in the Commons area, they need to proceed to the practice gym. ● Take attendance and report by phone, all uned students to the superintendent’s office immediately. Continue to call until you speak to them. Please do not leave a message. If the phone is not available, use email to report students uned for to the superintendent. ● Students will turn desks on sides and use them as a barricade if necessary. ● Do not use the phones or cell phones unless you are reporting uned for students to the office, please. Do not jam our phone lines. ● Office personnel and custodians will lock the academic wing doors, stairwell doors, elevator and office doors for drills only. The will also check the rest rooms. ○ Go to designated safe area within your classrooms immediately. ○ Should have access to a telephone and a computer system, if possible. ○ Phone calls need to be brief. Do not give out information until verified by the building principal or law enforcement. ● All personnel need to wait for further instructions on how to proceed from this point. As of now, this plan has not been needed at Earlham. However, that doesn’t mean we should not keep it updated considering how many mass shootings take place in the United States. In order to update this plan, I would include options for teachers to use their discretion. Two years ago, all Earlham Staff underwent ALICE (Alert, Lockdown, Inform, Counter, Evacuate) training with a few of Iowa’s State Troopers. This training prepares individuals to handle the threat of an Active Shooter, and teaches individuals to participate in their own survival, while leading others to safety (ALICE Training Institute, 2016). ALICE allows teachers and students options including fighting back and fleeing, whereas traditional active shooter/intruder policies ask students, teachers, and other school staff to do exactly what Earlham’s current policy states, lock up and wait. In addition to updating Earlham’s policy with ALICE, I would include something about monitoring students use of cell phones. While it is important for students to be able to reach their parents, this can sometimes cause problems for schools, especially if an intruder is active in a

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

12

school. Parents could show up at the school, alert the media, and cause more harm than good, despite having good intentions. Along with updating a current policy, Earlham also does not have any plans spelled out for exactly what to do the day or two after a crisis, a week after, or even a month after. I think we should have guidelines to follow in case a situation does happen in Earlham and could learn something from other school districts such as Waukee and Southeast Polk, whom have experienced multiple tragedies and crises. Regardless, my superintendent has been “called out” due to my interest in school crisis intervention and management, so I’m hoping changes will take place this summer that will bring our procedures up to date. Collaboration Concerning Crisis Management and Intervention Finally, when speaking of crisis management and intervention, you cannot leave out some of the crucial people involved. As mentioned briefly before, school staff, students, and community are not the only ones impacted by crises. Collaboration is needed across the board in order for a school crisis to be handled properly. This means that when planning or prepping for a possible event, schools should think about what community can help them both during and after a crisis. This includes looking to other school districts and outside agencies for help concerning the mental health needs of students and staff, how to emergency responders, and so on. crisis. As mentioned in their presentation, the Waukee Grief Response Team knows exactly who to call and communicate with after a death. Instead of confining themselves to the services within their district, they reach out to other counselors, mental health providers, and other professionals in order to help assess the impact of trauma on their school. Agencies to for services could include mental health providers that the district already works with, like Orchard

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

13

Place, the local Area Education Agency, or other organizations such as Youth Emergency Services and Shelters, Amanda the Panda, and so on. For Earlham in an active shooter situation, this would mean ing the Earlham police department, as well as the volunteer fire department, and even state troopers since we are a small community. After the event, we would need to call in multiple school and mental health counselors to provide services to our students. We may also need to depend on community and restaurants to help provide food to families in suffering or for staff the day after the event. Additionally, after the event has ed, students still may need referred to outside services, so keeping in with those that help is crucial. Finally, in preparing for such a crisis, Earlham has to reach out to the broader Des Moines community in order to fully update our crises policies and procedures. We are a small school district with limited resources, which means we cannot handle certain situations on our own. Thankfully, I believe we live in a state and broader community that is willing to step in without being asked when needed. When you look at some of the tragedies other schools have faced in Des Moines, you note everyone that has come to help, even in the smallest ways possible. In conclusion, one of my favorite quotes by Fred Rogers seems fitting here. It reads, “When I was a boy and I would see scary things in the news, my mother would say to me, "Look for the helpers. You will always find people who are helping.” Collaboration during a crisis is key, for without it all people involved would crumble.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

14

References ALICE Training Institute (2016). The 1st Active Shooter Response Program. Retrieved from http://www.alicetraining.com/ Allen, M., Burt, K., Bryan, E., Carter, D., Orsi, R., & Durkan, L. (2002). School counselors’ preparation for and participation in crisis intervention. Professional School Counseling, 6, 96-102 American School Counselor Association (2007). Position Statement: Crisis/critical incident response in the schools. Alexandria, VA: Author. Christiansen, A. (2014) Nearly 100 more school shootings since Sandy Hook, report says. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/nearly-100-school-shootingssince-sandy-hook-report-says/ Egan, G. (2002). The skilled helper (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

CRISIS MANAGEMENT AND INTERVENTION

15

Eaton, Y., & Ertl, B. (2000). The comprehensive crisis intervention model of Community Integration, Inc. Crisis Services. In A. R. Roberts (Ed.), Crisis intervention handbook: Assessment, treatment, and research(2nd ed., pp. 373–387). New York: Oxford University Press. International Association of Chiefs of Police (n.d.) Guide for preventing and responding to school violence. Retrieved from http://www.theia.org/portals/0/pdfs/schoolviolence2.pdf Knox, K. S. & Roberts, A. R. (2005). Crisis Intervention and Crisis Team Models in Schools. 27(2), 93-100. Roberts, A. R. (2005). Bridging the past and present to the future of crisis intervention and crisis management. In A. R. Roberts (Ed.), Crisis intervention handbook: Assessment, treatment, and research(3rd ed., pp. 3–34). New York: Oxford University Press. Roberts, A. R. & Ottens, A. J. (2005). Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention 5(4):329-339; doi:10.1093/brief-treatment/mhi030

Stephan, S. H. & Lever, N. (n.d.) Resources for dealing with traumatic events in schools. Retrieved from http://c.ymcdn.com/sites/www.sswaa.org/resource/resmgr/imported/ListofTraumaResour ces.pdf Studer, J. R., Baker, C., & Camp, E. (2009). The perceptions of the roles of professional school counselors and school psychologists as perceived by educators. Manuscript submitted for publication. Studer, J. R. & Salter, S. E. (2010). The Role of the School Counselor in Crisis Planning and Intervention. Retrieved from http://www.counseling.org/resources/library/vistas/2010-VOnline/Article_92.pdf Wiger, D. E. & Harowski, K. J. (2003). Essentials of crisis counseling and intervention. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons Inc. Worldometers.com (20016). Current world population. Retireved from http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/