Ipl-case-digests-2019.docx 1f10u

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report 3b7i

Overview 3e4r5l

& View Ipl-case-digests-2019.docx as PDF for free.

More details w3441

- Words: 21,092

- Pages: 50

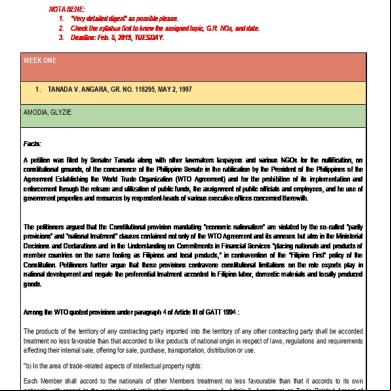

COPYRIGHT AND INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY LAWS BASED FROM JUDGE QUIRANTE’S SYLLABUS CASE DIGESTS 2019 NOTA BENE: 1. “Very detailed digest” as possible please. 2. Check the syllabus first to know the assigned topic, G.R. NOs, and date. 3. Deadline: Feb. 5, 2019, TUESDAY. WEEK ONE

1. TANADA V. ANGARA, GR. NO. 118295, MAY 2, 1997 AMODIA, GLYZIE

Facts: A petition was filed by Senator Tanada along with other lawmakers taxpayers and various NGOs for the nullification, on constitutional grounds, of the concurrence of the Philippine Senate in the ratification by the President of the Philippines of the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO Agreement) and for the prohibition of its implementation and enforcement through the release and utilization of public funds, the assignment of public officials and employees, and he use of government properties and resources by respondent-heads of various executive offices concerned therewith.

The petitioners argued that the Constitutional provision mandating “economic nationalism” are violated by the so-called “parity provisions” and “national treatment” clauses contained not only of the WTO Agreement and its annexes but also in the Ministerial Decisions and Declarations and in the Understanding on Commitments in Financial Services “placing nationals and products of member countries on the same footing as Filipinos and local products," in contravention of the "Filipino First" policy of the Constitution. Petitioners further argue that these provisions contravene constitutional limitations on the role exports play in national development and negate the preferential treatment accorded to Filipino labor, domestic materials and locally produced goods.

Among the WTO quoted provisions under paragraph 4 of Article III of GATT 1994 : The products of the territory of any contracting party imported into the territory of any other contracting party shall be accorded treatment no less favorable than that accorded to like products of national origin in respect of laws, regulations and requirements affecting their internal sale, offering for sale, purchase, transportation, distribution or use. "b) In the area of trade-related aspects of intellectual property rights: Each Member shall accord to the nationals of other treatment no less favourable than that it accords to its own nationals with regard to the protection of intellectual property . . . (par. 1, Article 3, Agreement on Trade-Related Aspect of Intellectual Property rights, Vol. 31, Uruguay Round, Legal Instruments, p. 25432

1

—-mao ra ni IPL related jud On the other hand, respondents through the Solicitor General counter (1) that such Charter provisions are not self-executing and merely set out general policies; (2) that these nationalistic portions of the Constitution invoked by petitioners should not be read in isolation but should be related to other relevant provisions of Art. XII, particularly Secs. 1 and 13 thereof; (3) that read properly, the cited WTO clauses do not conflict with the Constitution; and (4) that the WTO Agreement contains sufficient provisions to protect developing countries like the Philippines from the harshness of sudden trade liberalization. Issue/s: A. Whether the provisions of the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization contravene the provisions of Sec. 19, Article II, and Secs. 10 and 12, Article XII, all of the 1987 Philippine Constitution. B. Do the provisions of said agreements and its annexes limit, restrict, or impair the exercise of Legislative power by the Congress? Ruling: A. No. While the Constitution mandates a bias in favor of Filipino goods, services, labor and enterprises, at the same time, it recognizes the need for business exchange with the rest of the world on the bases of equality and reciprocity and limits protection of Filipino enterprises only against foreign competition and trade practices that are unfair. The Constitution did not intend to pursue an isolationist policy. It did not shut out foreign investments, goods and services in the development of the Philippine economy. While the Constitution does not encourage the unlimited entry of foreign goods, services and investments into the country, it does not prohibit them either. In fact, it allows an exchange on the basis of equality and reciprocity, frowning only on foreign competition that is unfair .

B. YES. While sovereignty has traditionally been deemed absolute and all-encoming on the domestic level, it is however subject to restrictions and limitations voluntarily agreed to by the Philippines, expressly or impliedly, as a member of the family of nations. In its Declaration of Principles and State Policies, the Constitution "adopts the generally accepted principles of international law as part of the law of the land, and adheres to the policy of peace, equality, justice, freedom, cooperation and amity, with all nations." By the doctrine of incorporation, the country is bound by generally accepted principles of international law, which are considered to be automatically part of our own laws. Adhering to one of the oldest and most fundamental rules in international law is pacta sunt servanda — international agreements must be performed in good faith. By their inherent nature, treaties really limit or restrict the absoluteness of sovereignty. By their voluntary act, nations may surrender some aspects of their state power in exchange for greater benefits granted by or derived from a convention or pact. As aptly put by John F. Kennedy, "Today, no nation can build its destiny alone. The age of self-sufficient nationalism is over. The age of interdependence is here." The Philippines has effectively agreed to limit the exercise of its sovereign powers of taxation, eminent domain and police power by entering into those treaties. The underlying consideration in this partial surrender of sovereignty is the reciprocal commitment of the other contracting states in granting the same privilege and immunities to the Philippines, its officials and its citizens. The same reciprocity characterizes the Philippine commitments under WTO-GATT.

P.S. This case is also a coverage for the other week, so pls also include the ruling about: 1. Requirement of Notice for Damages Sec. 80- for week 13----wa koy na find notice for damages

2

2. MIRPURI V. CA, GR. NO. 114508-55, NOV. 19, 1999 BANAAG, CREADZ (P.S. taas jud this digest bec daghan gi-assign na topic si atty ani na case) Facts: The Convention of Paris for the Protection of Industrial Property is a multi-lateral treaty which the Philippines bound itself to honor and enforce in this country. As to whether or not the treaty affords protection to a foreign corporation against a Philippine applicant for the registration of a similar trademark is the principal issue in this case. On June 15, 1970, Lolita Escobar, the predecessor-in-interest of petitioner Pribhdas J. Mirpuri, filed an application with the Bureau of Patents for the registration of the trademark "Barbizon" for use in brassieres and ladies undergarments. Escobar alleged that she had been manufacturing and selling these products under the firm name "L & BM Commercial" since March 3, 1970. Private respondent Barbizon Corporation, a corporation organized and doing business under the laws of New York, U.S.A., opposed the application. It claimed that: "The mark BARBIZON of respondent-applicant is confusingly similar to the trademark BARBIZON which opposer owns and has not abandoned. That opposer will be damaged by the registration of the mark BARBIZON and its business reputation and goodwill will suffer great and irreparable injury. That the respondent-applicant's use of the said mark BARBIZON which resembles the trademark used and owned by opposer, constitutes an unlawful appropriation of a mark previously used in the Philippines and not abandoned and therefore a statutory violation of Section 4 (d) of Republic Act No. 166, as amended.” On June 18, 1974, the Director of Patents rendered judgment giving due course to Escobar's application. Lolita Escobar was issued a certificate of registration for the trademark "Barbizon." Escobar later assigned all her rights and interest over the trademark to petitioner Pribhdas J. Mirpuri who, under his firm name then, the "Bonito Enterprises," was the sole and exclusive distributor of Escobar's "Barbizon" products. In 1979, however, Escobar failed to file with the Bureau of Patents the Affidavit of Use of the trademark required under Section 12 of Republic Act (R.A.) No. 166, the Philippine Trademark Law. Due to this failure, the Bureau of Patents cancelled Escobar's certificate of registration. On 1981, Escobar reapplied for registration of the cancelled trademark. Mirpuri filed his own application for registration of Escobar's trademark. Escobar later assigned her application to herein petitioner and this application was opposed by private respondent . Replying to private respondent's opposition, petitioner raised the defense of res judicata. On 1982, Escobar assigned to petitioner the use of the business name "Barbizon International." Petitioner ed the name with the Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) for which a certificate of registration was issued. Private respondent filed before the DTI a petition for cancellation of petitioner's business name. The DTI, cancelled petitioner's certificate of registration, and declared private respondent the owner and prior of the business name "Barbizon International." On April 1993, the Court of Appeals reversed the Director of Patents and ordered that the case be remanded to the Bureau of Patents for further proceedings.The Court of Appeals denied reconsideration of its decision. In the IPC, Escobar is given due course. Issue/s: Whether or not the herein opposer would probably be damaged by the registration of the trademark BARBIZON sought by the respondent-applicant on the ground that it so resembles the trademark BARBIZON allegedly used and owned by the former to be `likely to cause confusion, mistake or to deceive purchasers. Ruling:

3

Definition of Trademark- for week 7 and Functions of Trademark- for week 7 A "trademark" is defined under R.A. 166, the Trademark Law, as including "any word, name, symbol, emblem, sign or device or any combination thereof adopted and used by a manufacturer or merchant to identify his goods and distinguish them from those manufactured, sold or dealt in by others. This definition has been simplified in R.A. No. 8293, the Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines, which defines a "trademark" as "any visible sign capable of distinguishing goods. In Philippine jurisprudence, the function of a trademark is to point out distinctly the origin or ownership of the goods to which it is affixed; to secure to him, who has been instrumental in bringing into the market a superior article of merchandise, the fruit of his industry and skill; to assure the public that they are procuring the genuine article; to prevent fraud and imposition; and to protect the manufacturer against substitution and sale of an inferior and different article as his product. Modern authorities on trademark law view trademarks as performing three distinct functions: (1) they indicate origin or ownership of the articles to which they are attached; (2) they guarantee that those articles come up to a certain standard of quality; and (3) they the articles they symbolize. Historical Development of Trademark Law- for week 7 Before ruling on the issues of the case, there is need for a brief background on the function and historical development of trademarks and trademark law. Symbols have been used to identify the ownership or origin of articles for several centuries.As early as 5,000 B.C., markings on pottery have been found by archaeologists. Cave drawings in southwestern Europe show bison with symbols on their flanks.Archaeological discoveries of ancient Greek and Roman inscriptions on sculptural works, paintings, vases, precious stones, glassworks, bricks, etc. reveal some features which are thought to be marks or symbols. These marks were affixed by the creator or maker of the article, or by public authorities as indicators for the payment of tax, for disclosing state monopoly, or devices for the settlement of s between an entrepreneur and his workmen. In the Middle Ages, the use of many kinds of marks on a variety of goods was commonplace. Fifteenth century England saw the compulsory use of identifying marks in certain trades. There were the baker's mark on bread, bottlemaker's marks, smith's marks, tanner's marks, watermarks on paper, etc. Every guild had its own mark and every master belonging to it had a special mark of his own. The marks were not trademarks but police marks compulsorily imposed by the sovereign to let the public know that the goods were not "foreign" goods smuggled into an area where the guild had a monopoly, as well as to aid in tracing defective work or poor craftsmanship to the artisan. For a similar reason, merchants also used merchants' marks. Merchants dealt in goods acquired from many sources and the marks enabled them to identify and reclaim their goods upon recovery after shipwreck or piracy. With constant use, the mark acquired popularity and became voluntarily adopted. It was not intended to create or continue monopoly but to give the customer an index or guarantee of quality. It was in the late 18th century when the industrial revolution gave rise to mass production and distribution of consumer goods that the mark became an important instrumentality of trade and commerce. By this time, trademarks did not merely identify the goods; they also indicated the goods to be of satisfactory quality, and thereby stimulated further purchases by the consuming public. Eventually, they came to symbolize the goodwill and business reputation of the owner of the product and became a property right protected by law.[ The common law developed the doctrine of trademarks and tradenames "to prevent a person from palming off his goods as another's, from getting another's business or injuring his reputation by unfair means, and, from defrauding the public." Subsequently, England and the United States enacted national legislation on trademarks as part of the law regulating unfair trade. It became the right of the trademark owner to exclude others from the use of his mark, or of a confusingly similar mark where confusion resulted in diversion of trade or financial injury. At the same time, the trademark served as a warning against the imitation or faking of products to prevent the imposition of fraud upon the public. Today, the trademark is not merely a symbol of origin and goodwill; it is often the most effective agent for the actual creation and protection of goodwill. It imprints upon the public mind an anonymous and impersonal guaranty of satisfaction, creating a desire

4

for further satisfaction. In other words, the mark actually sells the goods.The mark has become the "silent salesman," the conduit through which direct between the trademark owner and the consumer is assured. It has invaded popular culture in ways never anticipated that it has become a more convincing selling point than even the quality of the article to which it refers. In the last half century, the unparalleled growth of industry and the rapid development of communications technology have enabled trademarks, tradenames and other distinctive signs of a product to penetrate regions where the owner does not actually manufacture or sell the product itself. Goodwill is no longer confined to the territory of actual market penetration; it extends to zones where the marked article has been fixed in the public mind through advertising. Whether in the print, broadcast or electronic communications medium, particularly on the Internet, advertising has paved the way for growth and expansion of the product by creating and earning a reputation that crosses over borders, virtually turning the whole world into one vast marketplace. -------------------------------------------------------------Private respondent argues, the prior use and registration of the trademark in the United States and other countries worldwide, prior use in the Philippines, and the fraudulent registration of the mark in violation of Article 189 of the Revised Penal Code. Private respondent also cited protection of the trademark under the Convention of Paris for the Protection of Industrial Property, specifically Article 6bis thereof, and the implementation of Article 6bis by two Memoranda of the Minister of Trade and Industry to the Director of Patents, as well as Executive Order (E.O.) No. 913. The Convention of Paris for the Protection of Industrial Property, otherwise known as the Paris Convention, is a multilateral treaty that seeks to protect industrial property consisting of patents, utility models, industrial designs, trademarks, service marks, trade names and indications of source or appellations of origin, and at the same time aims to repress unfair competition. The Convention is essentially a compact among various countries which, as of the Union, have pledged to accord to citizens of the other member countries trademark and other rights comparable to those accorded their own citizens by their domestic laws for an effective protection against unfair competition. In short, foreign nationals are to be given the same treatment in each of the member countries as that country makes available to its own citizens. Nationals of the various member nations are thus assured of a certain minimum of international protection of their industrial property. The Philippines, through its Senate, concurred on May 10, 1965.]The Philippines' adhesion became effective on September 27, 1965, and from this date, the country obligated itself to honor and enforce the provisions of the Convention. In the case at bar, private respondent anchors its cause of action on the first paragraph of Article 6bis of the Paris Convention which reads as follows: "Article 6bis (1) The countries of the Union undertake, either istratively if their legislation so permits, or at the request of an interested party, to refuse or to cancel the registration and to prohibit the use, of a trademark which constitutes a reproduction, an imitation, or a translation, liable to create confusion, of a mark considered by the competent authority of the country of registration or use to be well-known in that country as being already the mark of a person entitled to the benefits of this Convention and used for identical or similar goods. These provisions shall also apply when the essential part of the mark constitutes a reproduction of any such well-known mark or an imitation liable to create confusion therewith. Xxxxxxxx Well-Known Marks Sec. 147.2- for week 9 This Article governs protection of well-known trademarks. Under the first paragraph, each country of the Union bound itself to undertake to refuse or cancel the registration, and prohibit the use of a trademark which is a reproduction, imitation or translation, or any essential part of which trademark constitutes a reproduction, liable to create confusion, of a mark considered by the competent authority of the country where protection is sought, to be well-known in the country as being already the mark of a person entitled to the benefits of the Convention, and used for identical or similar goods. Article 6bis is a self-executing provision and does not require legislative enactment to give it effect in the member country. It may be applied directly by the tribunals and officials of each member country by the mere publication or proclamation of the Convention, after its ratification according to the public law of each state and the order for its execution.

5

The essential requirement under Article 6bis is that the trademark to be protected must be "well-known" in the country where protection is sought. The power to determine whether a trademark is well-known lies in the "competent authority of the country of registration or use." This competent authority would be either the ing authority if it has the power to decide this, or the courts of the country in question if the issue comes before a court. Pursuant to Article 6bis, on November 20, 1980, then Minister Luis Villafuerte of the Ministry of Trade issued a Memorandum to the Director of Patents. Three years later, then Minister Roberto Ongpin issued another Memorandum to the Director of Patents. In the Villafuerte Memorandum, the Minister of Trade instructed the Director of Patents to reject all pending applications for Philippine registration of signature and other world-famous trademarks by applicants other than their original owners or s. The Minister enumerated several internationally-known trademarks and ordered the Director of Patents to require Philippine registrants of such marks to surrender their certificates of registration. In the Ongpin Memorandum, the Minister of Trade and Industry did not enumerate well-known trademarks but laid down guidelines for the Director of Patents to observe in determining whether a trademark is entitled to protection as a well-known mark in the Philippines under Article 6bis of the Paris Convention. This was to be established through Philippine Patent Office procedures in inter partesand ex parte cases pursuant to the criteria enumerated therein. The Philippine Patent Office was ordered to refuse applications for, or cancel the registration of, trademarks which constitute a reproduction, translation or imitation of a trademark owned by a person who is a citizen of a member of the Union. All pending applications for registration of worldfamous trademarks by persons other than their original owners were to be rejected forthwith. Both the Villafuerte and Ongpin Memoranda were sustained by the Supreme Court in the 1984 landmark case of La Chemise Lacoste, S.A. v. Fernandez. This court ruled therein that under the provisions of Article 6bis of the Paris Convention, the Minister of Trade and Industry was the "competent authority" to determine whether a trademark is well-known in this country. The Villafuerte Memorandum was issued in 1980, i.e., fifteen (15) years after the adoption of the Paris Convention in 1965. In the case at bar, the first inter partes case, IPC No. 686, was filed in 1970, before the Villafuerte Memorandum but five (5) years after the effectivity of the Paris Convention. Article 6bis was already in effect five years before the first case was instituted. Private respondent, however, did not cite the protection of Article 6bis, neither did it mention the Paris Convention at all. It was only in 1981 when IPC No. 2049 was instituted that the Paris Convention and the Villafuerte Memorandum, and, during the pendency of the case, the 1983 Ongpin Memorandum were invoked by private respondent. The Solicitor General argues that the issue of whether the protection of Article 6bis of the Convention and the two Memoranda is barred by res judicata has already been answered in Wolverine Worldwide, Inc. v. Court of Appeals. In this case, petitioner Wolverine, a foreign corporation, filed with the Philippine Patent Office a petition for cancellation of the registration certificate of private respondent, a Filipino citizen, for the trademark "Hush Puppies" and "Dog Device." Petitioner alleged that it was the registrant of the internationally-known trademark in the United States and other countries, and cited protection under the Paris Convention and the Ongpin Memorandum. The petition was dismissed by the Patent Office on the ground of res judicata. It was found that in 1973 petitioner's predecessor-in-interest filed two petitions for cancellation of the same trademark against respondent's predecessor-in-interest. The Patent Office dismissed the petitions, ordered the cancellation of registration of petitioner's trademark, and gave due course to respondent's application for registration. This decision was sustained by the Court of Appeals, which decision was not elevated to us and became final and executory. It is also noted that the oppositions in the first and second cases are based on different laws. The opposition in IPC No. 686 was based on specific provisions of the Trademark Law, i.e., Section 4 (d) on confusing similarity of trademarks and Section 8 on the requisite damage to file an opposition to a petition for registration. The opposition in IPC No. 2049 invoked the Paris Convention, particularly Article 6bis thereof, E.O. No. 913 and the two Memoranda of the Minister of Trade and Industry. This opposition also invoked Article 189 of the Revised Penal Code which is a statute totally different from the Trademark Law. [ Causes of action which are distinct and independent from each other, although arising out of the same contract, transaction, or state of facts, may be sued on separately, recovery on one being no bar to subsequent actions on others. The mere fact that the same relief is sought in the subsequent action will not render the judgment in the prior action operative as res judicata, such as where the two actions are based on different statutes. Res judicata therefore does not apply to the instant case and respondent Court of Appeals did not err in so ruling. Functions of Trademark- for week 7 and

6

Laws that are repealed by The Intellectual Property Code-for week 1 Intellectual and industrial property rights cases are not simple property cases. Trademarks deal with the psychological function of symbols and the effect of these symbols on the public at large. Trademarks play a significant role in communication, commerce and trade, and serve valuable and interrelated business functions, both nationally and internationally. For this reason, all agreements concerning industrial property, like those on trademarks and tradenames, are intimately connected with economic development. Industrial property encourages investments in new ideas and inventions and stimulates creative efforts for the satisfaction of human needs. They speed up transfer of technology and industrialization, and thereby bring about social and economic progress. These advantages have been acknowledged by the Philippine government itself. The Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines declares that "an effective intellectual and industrial property system is vital to the development of domestic and creative activity, facilitates transfer of technology, it attracts foreign investments, and ensures market access for our products.” The Intellectual Property Code took effect on January 1, 1998 and by its express provision, repealed the Trademark Law, the Patent Law, Articles 188 and 189 of the Revised Penal Code, the Decree on Intellectual Property, and the Decree on Compulsory Reprinting of Foreign Textbooks. The Code was enacted to strengthen the intellectual and industrial property system in the Philippines as mandated by the country's accession to the Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organization (WTO).

3. SAMSON V. DAWAY, GR. NO. 160054-55, JULY 21, 2004 CALDERON, CHATCH Facts: Issue/s: Ruling: 4. TWENTIETH CENTURY MUSIC CORP V. AIKEN, 422 U.S. 151 GARRIDO, NURISSA Facts:

Facts: The respondent George Aiken owns and operates a small fast-service food shop in downtown Pittsburgh, Pa., known as "George Aiken's Chicken." A radio with outlets to four speakers in the ceiling receives broadcasts of music and other normal radio programing at the restaurant. On March 11, 1972, broadcasts of two copyrighted musical compositions were received on the radio from a local station while several customers were in Aiken's establishment. Petitioner Twentieth Century Music Corp. owns the copyright on one of these songs, "The More I See You"; petitioner Mary Bourne the copyright on the other, "Me and My Shadow." Petitioners are of the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP), an association that licenses the performing rights of its to their copyrighted works. The station that broadcast the petitioners' songs was licensed by ASCAP to broadcast them. Aiken, however, did not hold a license from ASCAP. The petitioners sued Aiken in the United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania to recover for

7

copyright infringement. Their complaint alleged that the radio reception in Aiken's restaurant of the licensed broadcasts infringed their exclusive rights to "perform" their copyrighted works in public for profit. The District Judge agreed, and granted statutory monetary awards for each infringement. The United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit reversed that judgment holding that the petitioners' claims against the respondent were foreclosed by this Court's decisions in Fortnightly Corp. v. United Artists and Teleprompter Corp. v. CBS. We granted certiorari. Issue: Whether the reception of a radio broadcast of a copyrighted musical composition can constitute copyright infringement, when the copyright owner has licensed the broadcaster to perform the composition publicly for profit. Ruling: "The Copyright Act does not give a copyright holder control over all uses of his copyrighted work. Instead, 1 of the Act enumerates several `rights' that are made `exclusive' to the holder of the copyright. If a person, without authorization from the copyright holder, puts a copyrighted work to a use within the scope of one of these `exclusive rights,' he infringes the copyright. If he puts the work to a use not enumerated in 1, he does not infringe." Accordingly, if an unlicensed use of a copyrighted work does not conflict with an "exclusive" right conferred by the statute, it is no infringement of the holder's rights. The limited scope of the copyright holder's statutory monopoly, like the limited copyright duration required by the Constitution, 5 reflects a balance of competing claims upon the public interest: Creative work is to be encouraged and rewarded, but private motivation must ultimately serve the cause of promoting broad public availability of literature, music, and the other arts. The immediate effect of our copyright law is to secure a fair return for an "author's" creative labor. But the ultimate aim is, by this incentive, to stimulate artistic creativity for the general public good. The precise statutory issue in the present case is whether Aiken infringed upon the petitioners' exclusive right, under the Copyright Act of 1909. 17 U.S.C. 1 (e), "[t]o perform the copyrighted work publicly for profit." We may assume that the radio reception of the musical compositions in Aiken's restaurant occurred "publicly for profit." The dispositive question, therefore, is whether this radio reception constituted a "performance" of the copyrighted works. A performance, in our judgment, is no less public because the listeners are unable to communicate with one another, or are not assembled within an inclosure, or gathered together in some open stadium or park or other public place. Nor can a performance, in our judgment, be deemed private because each listener may enjoy it alone in the privacy of his home. Radio broadcasting is intended to, and in fact does, reach a very much larger number of the public at the moment of the rendition than any other medium of performance. The artist is consciously addressing a great, though unseen and widely scattered, audience, and is therefore participating in a public performance. As the Court of Appeals in this case perceived, this Court has in two recent decisions explicitly disavowed the view that the reception of an electronic broadcast can constitute a performance, when the broadcaster himself is licensed to perform the copyrighted material that he broadcasts. (Fortnightly and Teleprompter) The Fortnightly and Teleprompter cases, to be sure, involved television, not radio, and the copyrighted materials there in issue were literary and dramatic works, not musical compositions. But, as the Court of Appeals correctly observed: "[I]f Fortnightly, with its elaborate CATV plant and Teleprompter with its even more sophisticated and extended technological and programming facilities were not `performing,' then logic dictates that no `performance' resulted when the [respondent] merely activated his restaurant radio." To hold in this case that the respondent Aiken "performed" the petitioners' copyrighted works would thus require us to

8

overrule two very recent decisions of this Court. But such a holding would more than offend the principles of stare decisis; it would result in a regime of copyright law that would be both wholly unenforceable and highly inequitable. The practical unenforceability of a ruling that all of those in Aiken's position are copyright infringers is self-evident. One has only to consider the countless business establishments in this country with radio or television sets on their premises - bars, beauty shops, cafeterias, car washes, dentists' offices, and drive-ins - to realize the total futility of any evenhanded effort on the part of copyright holders to license even a substantial percentage of them. And a ruling that a radio listener "performs" every broadcast that he receives would be highly inequitable for two distinct reasons. First, a person in Aiken's position would have no sure way of protecting himself from liability for copyright infringement except by keeping his radio set turned off. For even if he secured a license from ASCAP, he would have no way of either foreseeing or controlling the broadcast of compositions whose copyright was held by someone else. Secondly, to hold that [422 U.S. 151, 163] all in Aiken's position "performed" these musical compositions would be to authorize the sale of an untold number of licenses for what is basically a single public rendition of a copyrighted work. The exaction of such multiple tribute would go far beyond what is required for the economic protection of copyright owners, 14 and would be wholly at odds with the balanced congressional purpose behind 17 U.S.C. 1 (e): To accomplish the double purpose of securing to the composer an adequate return for all use made of his composition and at the same time prevent the formation of oppressive monopolies, which might be founded upon the very rights granted to the composer for the purpose of protecting his interests.

5. FEIST PUBLICATIONS, INC. V. RURAL TELE. SERVS. CO., 499 U.S. 340, 1991 GO, SARAH Facts: Respondent Rural Telephone Service Company is a certified public utility that provides telephone service to several communities in northwest Kansas. It is subject to a state regulation that requires all telephone companies operating in Kansas to issue annually an updated telephone directory as a condition of its monopoly franchise. Rural publishes a typical telephone directory, consisting of white pages and yellow pages. The white pages list in alphabetical order the names of Rural's subscribers, together with their towns and telephone numbers. It obtains data for the directory from subscribers, who must provide their names and addresses to obtain telephone service. Petitioner Feist Publications, Inc., is a publishing company that specializes in area-wide telephone directories covering a much larger geographic range than directories such as Rural's. Unlike a typical directory, which covers only a particular calling area, Feist's area-wide directories cover a much larger geographical range, reducing the need to call directory assistance or consult multiple directories. Feist is not a telephone company, let alone one with monopoly status, and therefore lacks independent access to any subscriber information. To obtain white pages listings for its area-wide directory, Feist approached each of the 11 telephone companies operating in northwest Kansas and offered to pay for the right to use its white pages listings. Of the 11 telephone companies, only Rural refused to license its listings to Feist. Rural's refusal created a problem for Feist, as omitting these listings would have left a gaping hole in its area-wide directory, rendering it less attractive to potential yellow pages rs. Feist extracted the listings it needed from Rural's white pages without Rural's consent. Although Feist altered many of Rural's listings, several were identical to listings in Rural's white pages. Rural sued for copyright infringement in the District Court for the District of Kansas, taking the position that Feist, in compiling its own directory, could not use the information contained in Rural's white pages. Rural asserted that Feist's employees were obliged to travel door-to-door or conduct a telephone survey to discover the same information for themselves. Feist responded that such efforts were economically impractical and, in any event, unnecessary, because the information copied

9

was beyond the scope of copyright protection. The District Court granted summary judgment to Rural in its copyright infringement suit, holding that telephone directories are copyrightable. The Court of Appeals affirmed. Issue/s: Whether or not the copyright in Rural's directory protects the names, towns, and telephone numbers copied by Feist. Ruling: NO. It is this bedrock principle of copyright that mandates the law's seemingly disparate treatment of facts and factual compilations. "No one may claim originality as to facts." This is because facts do not owe their origin to an act of authorship. The distinction is one between creation and discovery: the first person to find and report a particular fact has not created the fact; he or she has merely discovered its existence. To borrow from Burrow-Giles, one who discovers a fact is not its "maker" or "originator." "The discoverer merely finds and records." Census-takers, for example, do not "create" the population figures that emerge from their efforts; in a sense, they copy these figures from the world around them. This inevitably means that the copyright in a factual compilation is thin. Notwithstanding a valid copyright, a subsequent compiler remains free to use the facts contained in another's publication to aid in preparing a competing work, so long as the competing work does not feature the same selection and arrangement. As one commentator explains it:"No matter how much original authorship the work displays, the facts and ideas it exposes are free for the taking. . . . The very same facts and ideas may be divorced from the context imposed by the author, and restated or reshuffled by second comers, even if the author was the first to discover the facts or to propose the ideas." The Court has long recognized that the FACT/EXPRESSION DICHOTOMY limits severely the scope of protection in fact-based works. More than a century ago, the Court observed: "The very object of publishing a book on science or the useful arts is to communicate to the world the useful knowledge which it contains. But this object would be frustrated if the knowledge could not be used without incurring the guilt of piracy of the book." This was reiterated in Harper & Row: "No author may copyright facts or ideas. The copyright is limited to those aspects of the work -- termed 'expression' -- that display the stamp of the author's originality." It is also important to take note that the SWEAT OF THE BROW DOCTRINE (an author gains rights through simple diligence during the creation of a work, such as a database, or a directory) was already abandoned. To reiterate, the primary objective of copyright is not to reward the labor of authors, but "to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts." In this case, the names, towns, and telephone numbers copied by Feist from Rural’s directory are mere facts which Rural did not author but merely collected. Rural’s copyright only protects the compilation which is the directory itself but not the facts contained therein. Thus, Feist did not infringe Rural’s copyright in copying said facts from Rural’s directory - names, towns, and telephone numbers. 6. PEARL DEAN INC., VS SHOEMART INC.., G.R. NO. 148222, AUG. 15, 2003 GORGONIO, JENNY Facts: Pearl and Dean (Phil.), Inc. (PDI) is engaged in the manufacture of advertising display units simply referred to as light boxes. PDI was able to secure a Certificate of Copyright Registration, the advertising light boxes were marketed under the trademark “Poster Ads”. PDI negotiated with defendant-appellant Shoemart, Inc. (SMI) for the lease and installation of the light boxes in certain SM Makati and SM Cubao. PDI submitted for signature the contracts covering both stores, but only the contract for SM Makati, however, was returned signed. Eventually, SMI’s informed PDI that it was rescinding the contract for SM Makati due to non-performance of the thereof. Years later, PDI found out that exact copies of its light boxes were installed at different SM stores. It was further discovered that SMI’s sister company North Edsa Marketing Inc. (NEMI), sells advertising space in lighted display units located in SMI’s different

10

branches. PDI sent a letter to both SMI and NEMI ening them to cease using the subject light boxes, remove the same from SMI’s establishments and to discontinue the use of the trademark “Poster Ads,” as well as the payment of compensatory damages. Claiming that both SMI and NEMI failed to meet all its demands, PDI filed this instant case for infringement of trademark and copyright, unfair competition and damages. SMI maintained that it independently developed its poster s using commonly known techniques and available technology, without notice of or reference to PDI’s copyright. SMI noted that the registration of the mark “Poster Ads” was only for stationeries such as letterheads, envelopes, and the like. Besides, according to SMI, the word “Poster Ads” is a generic term which cannot be appropriated as a trademark, and, as such, registration of such mark is invalid. On this basis, SMI, aside from praying for the dismissal of the case, also counterclaimed for moral, actual and exemplary damages and for the cancellation of PDI’s Certification of Copyright Registration, and Certificate of Trademark Registration. Issue/s:

1. Whether the the light box depicted in such engineering drawings ipso facto also protected by such copyright. 2. Whether there was a patent infringement. 3. Whether the owner of a ed trademark legally prevent others from using such trademark if it abbreviation of a term descriptive of his goods, services or business?

is a mere

Ruling:

ON THE ISSUE OF COPYRIGHT INFRINGEMENT

The Court of Appeals correctly held that the copyright was limited to the drawings alone and not to the light box itself. Although petitioner’s copyright certificate was entitled “Advertising Display Units” (which depicted the box-type electrical devices), its claim of copyright infringement cannot be sustained. Copyright, in the strict sense of the term, is purely a statutory right. Accordingly, it can cover only the works falling within the statutory enumeration or description. Even as we find that P & D indeed owned a valid copyright, the same could have referred only to the technical drawings within the category of “pictorial illustrations.” It could not have possibly stretched out to include the underlying light box. The light box was not a literary or artistic piece which could be copyrighted under the copyright law. During the trial, the president of P & D himself itted that the light box was neither a literary not an artistic work but an engineering or marketing invention.The Court reiterated the ruling in the case of Kho vs. Court of Appeals, differentiating patents, copyrights and trademarks, namely: A trademark is any visible sign capable of distinguishing the goods (trademark) or services (service mark) of an enterprise and shall include a stamped or marked container of goods. In relation thereto, a trade name means the name or designation identifying or distinguishing an enterprise. Meanwhile, the scope of a copyright is confined to literary and artistic works which are original intellectual creations in the literary and artistic domain protected from the moment of their creation. Patentable inventions, on the other hand, refer to any technical solution of a problem in any field of human activity which is new, involves an

11

inventive step and is industrially applicable. ON THE ISSUE OF PATENT INFRINGEMENT Petitioner never secured a patent for the light boxes. It therefore acquired no patent rights which and could not legally prevent anyone from manufacturing or commercially using the contraption. To be able to effectively and legally preclude others from copying and profiting from the invention, a patent is a primordial requirement. No patent, no protection. ON THE ISSUE OF TRADEMARK INFRINGEMENT On the issue of trademark infringement, the petitioner’s president said “Poster Ads” was a contraction of “poster advertising.” P & D was able to secure a trademark certificate for it, but one where the goods specified were “stationeries such as letterheads, envelopes, calling cards and newsletters.”Petitioner itted it did not commercially engage in or market these goods. On the contrary, it dealt in electrically operated backlit advertising units which, however, were not at all specified in the trademark certificate. Assuming arguendo that “Poster Ads” could validly qualify as a trademark, the failure of P & D to secure a trademark registration for specific use on the light boxes meant that there could not have been any trademark infringement since registration was an essential element thereof. ON THE ISSUE OF UNFAIR COMPETITION There was no evidence that P & D’s use of “Poster Ads” was distinctive or well-known. As noted by the Court of Appeals, petitioner’s expert witnesses himself had testified that ” ‘Poster Ads’ was too generic a name. So it was difficult to identify it with any company, honestly speaking.”This crucial ission that “Poster Ads” could not be associated with P & D showed that, in the mind of the public, the goods and services carrying the trademark “Poster Ads” could not be distinguished from the goods and services of other entities. “Poster Ads” was generic and incapable of being used as a trademark because it was used in the field of poster advertising, the very business engaged in by petitioner. “Secondary meaning” means that a word or phrase originally incapable of exclusive appropriation with reference to an article in the market might nevertheless have been used for so long and so exclusively by one producer with reference to his article that, in the trade and to that branch of the purchasing public, the word or phrase has come to mean that the article was his property. The petition is DENIED. P.S. This case is also a coverage for the other weeks, so pls also include the ruling about: 1. Copyright or Economic Rights (Sec. 177) - for Week 3 (No mention of “economic rights” and “Sec 177” in the ruling. For “copyright”, pls see above.) 2. Literary and artistic works and derivative work (sec. 221)- for week 6 (No mention of “derivative works” and “Sec 221” in the ruling. For “literary & artistic works”, pls see above.) 7. PEST MGMT ASSOC. OF THE PH V. FERTILIZER AND PESTICIDE, G.R. NO. 156041, FEB 21, 2007 GORGONIO, KIM Facts: The Pest Management Association of the Philippines (PMAP) filed a Petition for Declaratory Relief With Prayer for Issuance of A Writ of Preliminary Injunction and /or Temporary Restraining Order with the RTC on January 4, 2002. PMAP is a non-stock

12

corporation duly organized and existing under the laws of the Philippines which is duly licensed by the respondent, Fertilizer and Pesticide Authority (FPA). PMAP questioned the validity of Section 3.12 of the 1987 Pesticide Regulatory Policies and Implementing Guidelines, which provides thus: 3.12 Protection of Proprietary Data Data submitted to the first full or conditional registration of a pesticide active ingredient in the Philippines will be granted proprietary protection for a period of seven years from the date of such registration. During this period subsequent registrants may rely on these data only with third party authorization or otherwise must submit their own data. After this period, all data may be freely cited in of registration by any applicant, provided convincing proof is submitted that the product being ed is identical or substantially similar to any current ed pesticide, or differs only in ways that would not significantly increase the risk of unreasonable adverse effects. Issue: Whether or not FPA encroached upon the jurisdiction of the Intellectual Property Office Ruling: There is no encroachment upon the powers of the IPO granted under R.A. No. 8293, otherwise known as the Intellectual Property Code of the Philippines. Section 5 thereof enumerates the functions of the IPO. Nowhere in said provision does it state nor can it be inferred that the law intended the IPO to have the exclusive authority to protect or promote intellectual property rights in the Philippines. On the contrary, paragraph (g) of said Section even provides that the IPO shall “coordinate with other government agencies and the private sector efforts to formulate and implement plans and policies to strengthen the protection of intellectual property rights in the country." Clearly, R.A. No. 8293 recognizes that efforts to fully protect intellectual property rights cannot be undertaken by the IPO alone. Other agencies dealing with intellectual property rights are, therefore, not precluded from issuing policies, guidelines and regulations to give protection to such rights. The FPA emphasized that the provision on protection of proprietary data does not usurp the functions of the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) since a patent and data protection are two different matters. A patent prohibits all unlicensed making, using and selling of a particular product, while data protection accorded by the FPA merely prevents copying or unauthorized use of an applicant's data, but any other party may independently generate and use his own data. It is further argued that under Republic Act No. 8293 (R.A. No. 8293), the grant of power to the IPO to ister and implement State policies on intellectual property is not exclusionary as the IPO is even allowed to coordinate with other government agencies to formulate and implement plans and policies to strengthen the protection of intellectual property rights.

WEEK TWO 1. COLUMBIA PICTURES V. CA, 261 SCRA 144 (1996) GUANZON, ANGELI Facts: Issue/s: Ruling:

13

P.S. This case is also a coverage for the other weeks, so pls also include the ruling about: 1. Remedies for Infringement Sec 216- for week 6

2. CHING V. SALINAS, G.R. NO. 161295, JUNE 29, 2005 IBISATE, GEORLAN Facts: ● Petitioner Ching is a maker and manufacturer of a utility model, Leaf Spring Eye Bushing for Automobile, for which he holds certificates of copyright registration. Petitioner’s request to the NBI to apprehend and prosecute illegal manufacturers of his work led to the issuance of search warrants against respondent Salinas, alleged to be reproducing and distributing said models in violation of the IP Code. ● Respondent moved to quash the warrants on the ground that petitioner’s work is not artistic in nature and is a proper subject of a patent, not copyright. Petitioner insists that the IP Code protects a work from the moment of its creation regardless of its nature or purpose. The trial court quashed the warrants. Petitioner argues that the copyright certificates over the model are prima facie evidence of its validity. CA affirmed the trial court’s decision. Issue/s: (1) Whether or not petitioner’s model is an artistic work subject to copyright protection. (2) Whether or not petitioner is entitled to copyright protection on the basis of the certificates of registration issued to it Ruling: (1) NO. As gleaned from the specifications appended to the application for a copyright certificate filed by the petitioner, the said Leaf Spring Eye Bushing for Automobile and Vehicle Bearing Cushion are merely utility models. As gleaned from the description of the models and their objectives, these articles are useful articles which are defined as one having an intrinsic utilitarian function that is not merely to portray the appearance of the article or to convey information. Plainly, these are not literary or artistic works. They are not intellectual creations in the literary and artistic domain, or works of applied art. They are certainly not ornamental designs or one having decorative quality or value. Indeed, while works of applied art, original intellectual, literary and artistic works are copyrightable, useful articles and works of industrial design are not. A useful article may be copyrightable only if and only to the extent that such design incorporates pictorial, graphic, or sculptural features that can be identified separately from, and are capable of existing independently of the utilitarian aspects of the article. In this case, the bushing and cushion are not works of art. They are, as the petitioner himself itted, utility models which may be the subject of a patent. (2) NO. No copyright granted by law can be said to arise in favor of the petitioner despite the issuance of the certificates of copyright registration and the deposit of the Leaf Spring Eye Bushing and Vehicle Bearing Cushion. Indeed, in Joaquin, Jr. v. Drilon and Pearl & Dean (Phil.), Incorporated v. Shoemart, Incorporated, the Court ruled that: Copyright, in the strict sense of the term, is purely a statutory right. It is a new or independent right granted by the statute, and not simply a pre-existing right regulated by it. Being a statutory grant, the rights are only such as the statute confers, and may be obtained and enjoyed only with respect to the subjects and by the persons, and on and conditions specified in the statute. Accordingly, it can cover only the works falling within the statutory enumeration or description. That the works of the petitioner may be the proper subject of a patent does not entitle him to the issuance of a search warrant for violation of copyright laws. In Kho v. Court of Appeals and Pearl & Dean (Phil.), Incorporated v. Shoemart, Incorporated, the Court ruled that these copyright and patent rights are completely distinct and separate from one another, and the protection afforded by one cannot be used interchangeably to cover items or works that exclusively pertain to the others. 3. OLANO V. LIM ENG CO., G.R. NO. 185835, MARCH 14, 2016

14

RAGAY, CD Facts: The petitioners are the officers and/or directors of Metrotech Steel Industries, Inc. (Metrotech). Lim Eng Co (respondent), on the other hand, is the Chairman of LEC Steel Manufacturing Corporation (LEC), a company which specializes in architectural metal manufacturing. LEC was subcontracted by Ski-First Balfour t Venture (SKI-FB), the project’s contractor, to manufacture and install interior and exterior hatch doors for the 7th to 22nd floors of the Project based on the final shop plans/drawings that LEC has submitted to them. Sometime thereafter, LEC learned that Metrotech was also subcontracted to install interior and exterior hatch doors for the Project's 23rd to 41st floors. LEC demanded Metrotech to cease from infringing its intellectual property rights but Metrotech insisted that no copyright infringement was committed because the hatch doors it manufactured were patterned in accordance with the drawings provided by SKI-FB. LEC sought the assistance of the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) which in turn applied for a search warrant before the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Quezon City, Branch 24. It resulted in the confiscation of finished and unfinished metal hatch doors as well as machines used in fabricating and manufacturing hatch doors from the premises of Metrotech. On August 13, 2004, the respondent filed a Complaint-Affidavit before the DOJ against the petitioners for copyright infringement. In the meantime or on September 8, 2004, the RTC quashed the search warrant on the ground that copyright infringement was not established. The investigating prosecutor dismissed the respondent's complaint based on inadequate evidence. The respondent filed a petition for review before the DOJ but it was also denied. Upon the respondent's motion for reconsideration, however, the DOJ reversed the investigating prosecutor’s decision and directed the Chief State Prosecutor to file the appropriate information for copyright infringement against the petitioners ruling that there was copyright infringement. The petitioners moved for reconsideration which was granted declaring that the evidence on record did not establish probable cause because the subject hatch doors were plainly metal doors with functional components devoid of any aesthetic or artistic features. The respondent thereafter filed a motion for reconsideration but it was denied. The respondent then sought recourse before the CA via a petition for certiorari ascribing grave abuse of discretion on the part of the DOJ. CA granted the petition and reiterated its ruling by denying the petitioner’s motion for reconsideration. Hence, this petition. Issue/s: Whether or not there is copyright infringement. Ruling: No. Copyright infringement is committed by any person who shall use original literary or artistic works, or derivative works, without the copyright owner's consent in such a manner as to violate the foregoing copy and economic rights. To constitute infringement, the usurper must have copied or appropriated the original work of an author or copyright proprietor, absent copying, there can be no infringement of copyright. In this case, the respondent failed to substantiate the alleged reproduction of the drawings/sketches of hatch doors copyrighted under Certificate of Registration Nos. 1-2004-13 and 1-2004-14. There is no proof that the respondents reprinted the copyrighted sketches/drawings of LEC's hatch doors.

15

In addition, hatch doors were not artistic works within the meaning of copyright laws. A hatch door, by its nature is an object of utility. It is defined as a small door, small gate or an opening that resembles a window equipped with an escape for use in case of fire or emergency.64 It is thus by nature, functional and utilitarian serving as egress access during emergency. Verily then, the CA erred in holding that a probable cause for copyright infringement is imputable against the petitioners. Absent originality and copyrightability as elements of a valid copyright ownership, no infringement can subsist. Therefore, there is no copyright infringement. 4. LAKTAW V. PAGLINAWAN, 44 PHIL. 855 (1918) RIEL, RAFA Facts: Laktaw was the ed owner and author of a literary work entitled Diccionario Hispano-Tagalog published in Manila in 1889. He alleged that Paglinawan, without his consent, reproduced said literary work, inproperly copied the greater part thereof in work published by him and entitled Diccionariong Kastila-Tagalog. As such is in violation of Article 7 of the Law of January 10, 1879, on Intellectual Property, caused irreparable injuries to Laktaw. The trial court absolved Paglinawan holding that a comparison of the plaintiff’s dictionary with that of the defendant does not show that the latter is an improper copy of the former, which has been published and offered for sale by the plaintiff for about twenty-five years or more. For this reason, the plaintiff had no right of action and that the remedy sought by him could not be granted, as the court held. Issue/s: Whether Paglinawan infringed Laktaw’s copyright over the dictionary. Ruling: The reproduction of another’s dictionary without the owner’s consent does not constitute a violation of the Law on Intellectual Property. However, the protection of the law cannot be denied to the author of a dictionary, for although words are not the property of anybody, their definitions, the example that explain their sense, and the manner of expressing their different meanings, may constitute a special rule. The Court held that the reproduction by the defendant without the plaintiff’s consent of the Diccionario Hispano-Tagalog published and edited in Manila in 1889, by the publication of the Diccionariong Kastila-Tagalog, published in the same City in 1913, has caused the plaintiff damages. Thus, the Court reversed the trial court’s judgment. 5. JOAQUIN V. DRILON JR. , 302 SCRA 225 (1999) UGALDE, KENT Facts: Petitioner BJ Productions, Inc. (BJPI) is the holder/grantee of Certificate of Copyright No. M922, dated January 28, 1971, of Rhoda and Me, a dating game show aired from 1970 to 1977. BJPI submitted to the National Library an addendum to its certificate of copyright specifying the show's format and style of presentation. While watching television, petitioner Francisco Joaquin, Jr., president of BJPI, saw on RPN Channel 9 an episode of It's a Date, which was produced by IXL Productions, Inc. (IXL). On July 18, 1991, he wrote a letter to private respondent Gabriel M. Zosa, president and general manager of IXL, informing Zosa that BJPI had a copyright to Rhoda and Me and demanding that IXL discontinue airing It's a Date.

16

In his reply letter, Zosa apologized to petitioner Joaquin and requested a meeting to discuss a possible settlement. IXL, however, continued airing It's a Date, prompting petitioner Joaquin to send a second letter which he reiterated his demand and warned that, if IXL did not comply, he would endorse the matter to his attorneys for proper legal action. Meanwhile, private respondent Zosa sought to IXL's copyright to the first episode of It's a Date for which it was issued by the National Library a certificate of copyright on August 14, 1991. Petitioner filed a complaint for violation of P.D. No. 49 (DECREE ON INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY) against private respondent Zosa together with certain officers of RPN Channel 9, namely, William Esposo, Felipe Medina, and Casey Francisco, in RTC QC. However, Zosa sought a review of the resolution of the Assistant City Prosecutor before the Department of Justice. Secretary of Justice Franklin M. Drilon reversed the Assistant City Prosecutor's findings and directed him to move for the dismissal of the case against private respondents. Petitioner filed MR but was denied. Hence, petition to SC. Issue/s: Did Sec Drilon acted with grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction when: 1. He said that non-presentation of master tape is fatal to existence of probable cause to prove infringement, despite the fact that respondents never raised it? 2. He determined what is copyrightable, which should be within the exclusive jurisdiction of RTC? Ruling: 1. No. Section 4, Rule 112 of Revised Rules of Crim Pro provides “xxx If upon petition by a proper party, the Secretary of Justice reverses the resolution of the provincial or city fiscal or chief state prosecutor, he shall direct the fiscal concerned to file the corresponding information without conducting another preliminary investigation or to dismiss or move for dismissal of the complaint or information xxx” In reviewing resolutions of prosecutors, the Secretary of Justice is not precluded from considering errors, although unassigned, for the purpose of determining whether there is probable cause for filing cases in court. He must make his own finding of probable cause and is not confined to the issues raised by the parties during preliminary investigation. Moreover, his findings are not subject to review unless shown to have been made with grave abuse. What evidence was presented by both parties? During the preliminary investigation, petitioners and private respondents presented written descriptions of the formats of their respective televisions shows, on the basis of which the investigating prosecutor ruled: As may [be] gleaned from the evidence on record, the substance of the television productions complainant's "RHODA AND ME" and Zosa's "IT'S A DATE" is that two matches are made between a male and a female, both single, and the two couples are treated to a night or two of dining and/or dancing at the expense of the show. The major concepts of both shows is the same. Any difference appear mere variations of the major concepts. That there is an infringement on the copyright of the show "RHODA AND ME" both in content and in the execution of the video presentation are established because respondent's "IT'S A DATE" is practically an exact copy of complainant's "RHODA AND ME" because of substantial similarities

ISSUE ON PRESENTATION OF MASTER TAPE Petitioner alleged that they presented sufficient evidence which clearly establish the “linkages” between the copyrighted show and the infringing show. Hence, the 20th Century Fox Film Corporation case relied by Sec of justice is inapplicable because in

17

that case the trial court found that the affidavits of NBI agents, given in of the application for the search warrant, were insufficient without the master tape. 20th Century Fox Film Corpo case “The essence of a copyright infringement is the similarity or at least substantial similarity of the purported pirated works to the copyrighted work. Hence, the applicant must present to the court the copyrighted films to compare them with the purchased evidence of the video tapes allegedly pirated to determine whether the latter is an unauthorized reproduction of the former. This linkage of the copyrighted films to the pirated films must be established to satisfy the requirements of probable cause. Mere allegations as to the existence of the copyrighted films cannot serve as basis for the issuance of a search warrant” The ruling in above mentioned case was qualified in a later case of Columbia pictures Inc vs CA which says: “…the necessity for the presentation of the master tapes of the copyrighted films for the validity of search warrants should at most be understood to merely serve as a guidepost in determining the existence of probable cause in copyright infringement cases where there is doubt as to the true nexus between the master tape and the pirated copies.” Is the master tape really necessary? Yes! The court held that mere description by words of the general format of the two dating game shows is insufficient; the presentation of the master videotape in evidence was indispensable to the determination of the existence of probable cause because as Drilon said that a television show includes more than mere words can describe because it involves a whole spectrum of visuals and effects, video and audio, such that no similarity or dissimilarity may be found by merely describing the general copyright/format of both dating game shows

2. No. It does not preclude Sec of justice from making preliminary determination of this question but as a general rule, this legal question is for the court to make.

Discussion on being a statutory right Copyright, in the strict sense of the term, is purely a statutory right...Being a statutory grant, the rights are only such as the statute confers, and may be obtained and enjoyed only with respect to the subjects and by the persons, and on and conditions specified in the statute. Since copyright in published works is purely a statutory creation, a copyright may be obtained only for a work falling within the statutory enumeration or description.

So what now are copyrightable then? The court said that the format of a show is not copyrightable since it does not fall under any of the classifications enumerated under Sec 2 of PD 49 which is substantially the same with Sec 172 of RA 8293 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CODE. Section 2. The rights granted by this Decree shall, from the moment of creation, subsist with respect to any of the following classes of works: (A) Books, including composite and cyclopedic works, manuscripts, directories, and gazetteers; (B) Periodicals, including pamphlets and newspapers; (C) Lectures, sermons, addresses, dissertations prepared for oral delivery; (D) Letters; (E) Dramatic or dramatico-musical compositions; choreographic works and entertainments in dumb shows, the acting form of which is fixed in writing or otherwise;

18

(F) Musical compositions, with or without words; (G) Works of drawing, painting, architecture, sculpture, engraving, lithography, and other works of art; models or designs for works of art; (H) Reproductions of a work of art; (I) Original ornamental designs or models for articles of manufacture, whether or not patentable, and other works of applied art; (J) Maps, plans, sketches, and charts; (K) Drawings or plastic works of a scientific or technical character; (L) Photographic works and works produced by a process analogous to photography; lantern slides; (M) Cinematographic works and works produced by a process analogous to cinematography or any process for making audio-visual recordings; (N) Computer programs; (O) Prints, pictorial illustrations advertising copies, labels, tags, and box wraps; (P) Dramatizations, translations, adaptations, abridgements, arrangements and other alterations of literary, musical or artistic works or of works of the Philippine government as herein defined, which shall be protected as provided in Section 8 of this Decree. (Q) Collections of literary, scholarly, or artistic works or of works referred to in Section 9 of this Decree which by reason of the selection and arrangement of their contents constitute intellectual creations, the same to be protected as such in accordance with Section 8 of this Decree. (R) Other literary, scholarly, scientific and artistic works. This enumeration refers to finished works and not to concepts. The copyright does not extend to an idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such work. Thus, the new INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY CODE OF THE PHILIPPINES provides: SEC. 175. Unprotected Subject Matter. — Notwithstanding the provisions of Sections 172 and 173, no protection shall extend, under this law, to any idea, procedure, system, method or operation, concept, principle, discovery or mere data as such, even if they are expressed, explained, illustrated or embodied in a work; news of the day and other miscellaneous facts having the character of mere items of press information; or any official text of a legislative, istrative or legal nature, as well as any official translation thereof. HENCE, PETITION IS DISMISSED!

WEEK THREE 1. PEARL & DEAN INC. v. SHOEMART INC. supra Check previous case digest. 2. FILIPINO SOCIETY OF COMPOSERS V. TAN, 148 SCRA 461 (1987) AMODIA Facts:

19

Petitioner-appellant is a non-profit association of authors, composers and publishers. Said association is the owner of certain musical compositions among which are the songs entitled: "Dahil Sa Iyo," "Sapagkat Ikaw Ay Akin," "Sapagkat Kami Ay Tao Lamang" and "The Nearness Of You." The petitioner filed a complaint for infringement of copyright against the defendant, who is the operator of a restaurant known as “Alex Soda Foundation and Restaurant” where the above-mentioned compositions were allegedly played without any license or permission from them. They contended that playing or singing a musical composition is universally accepted as performing the musical composition and that playing and singing of copyrighted music in the soda fountain and restaurant of the defendant for the entertainment of the customers although the latter do not pay for the music but only for the food and drink constitute performance for profit under the Copyright Law.

Defendant-appellee, in his answer, countered that the complaint states no cause of action, that the mere singing and playing of songs and popular tunes even if they are copyrighted do not constitute an infringement.

Issue/s: I. Whether or not the playing and g of musical compositions which have been copyrighted under the provisions of the Copyright Law (Act 3134) inside the establishment of the defendant-appellee constitute a public performance for profit within the meaning and contemplation of the Copyright Law of the Philippines?

II. Assuming that there were indeed public performances for profit, whether or not appellee can be held liable therefor?

Ruling: I.

The SC conceded that indeed there were “public performances for profit.”

It has been held that "The playing of music in dine and dance establishment which was paid for by the public in purchases of food and drink constituted 'performance for profit' within a Copyright Law," (Buck, et al. v. Russon, No. 4489 25 F. Supp. 317).

In the case at bar, the combo that played for the playing and singing the musical compositions involved was paid as independent contractors. It is therefore obvious that the expenses entailed thereby are added to the overhead of the restaurant which are either eventually charged in the price of the food and drinks or to the overall total of additional income produced by the bigger volume of business which the entertainment was programmed to attract. It can therefore be concluded that the playing and singing of the combo in defendant’s restaurant constituted performance for profit contemplated by the Copyright Law.

II. However, the SC agreed with the defendant when it said that the composers of the contested musical compositions waived their right in favor of the general public when they allowed heir intellectual creations to become property of the public domain

20

before applying for the corresponding copyrights for the same. The Supreme Court has previously ruled that if the general public has made use of the object sought to be copyrighted for thirty (30) days prior to the copyright application the law deems the object to have been donated to the public domain and the same can no longer be copyrighted. A careful study of the records reveals that some of the songs in controversy became popular in radios, juke boxes, etc. long before registration, one had become popular twenty five (25) years prior to the year of the hearing and others appear to have been known and sang by the witnesses as early as 1965, or 3 years before the hearing in 1968. Under the circumstances, it is clear that the musical compositions in question had long become public property, and are therefore beyond the protection of the Copyright Law.

3. MALANG SANTOS V. MCCuLLOUGH PRINTING, 12 SCRA 321 (1964) BANAAG Facts: This is an action for damages based on the provisions of Articles 721 and 722 of the Civil Code of the Philippines, allegedly on the unauthorized use, adoption and appropriation by the defendant company of plaintiff's intellectual creation or artistic design for a Christmas Card. The design depicts "a Philippine rural Christmas time scene consisting of a woman and a child in a nipa hut adorned with a star-shaped lantern and a man astride a carabao, beside a tree, underneath which appears the plaintiff's pen name, Malang." The complaint alleges that plaintiff Mauro Malang Santos designed for former Ambassador Felino Neri, for his personal Christmas Card greetings for the year 1959, the artistic motif in question. The following year the defendant McCullough Printing Company, without the knowledge and authority of plaintiff, displayed the very design in its album of Christmas cards and offered it for sale, for a price. Defendant in answer to the complaint, moved for a dismissal of the action claiming that — (1) The design claimed does not contain a clear notice that it belonged to him and that he prohibited its use by others; (2) The design in question has been published but does not contain a notice of copyright, as in fact it had never been copyrighted by the plaintiff. The lower court rendered judgment “that the artist acquires ownership of the product of his art. At the time of its creation, he has the absolute dominion over it. To help the author protect his rights the copyright law was enacted.The plaintiff in this case did not choose to protect his intellectual creation by a copyright. The fact that the design was used in the Christmas card of Ambassador Neri who distributed copies thereof among his friends during the Christmas season, shows that the, same was published. That unless satisfactorily explained, a delay in applying for a copyright, of more than thirty days from the date of its publication, converts the property to one of public domain. Since the name of the author appears in each of the alleged infringing copies of the intellectual creation, the defendant may not be said to have pirated the work nor guilty of plagiarism. Consequently, the complaint does not state a cause of action against the defendant. Hence, the lower court dismissed the complaint. Issue/s: (1) Whether plaintiff is entitled to protection, notwithstanding the, fact that he has not copyrighted his design; (2) Whether the publication is limited, so as to prohibit its use by others, or it is general publication, and (3) Whether the provisions of the Civil Code or the Copyright Law should apply in the case.

21