Constitutional Law 1 Digests Part 2 3j1o3r

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report 3b7i

Overview 3e4r5l

& View Constitutional Law 1 Digests Part 2 as PDF for free.

More details w3441

- Words: 155,581

- Pages: 391

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019

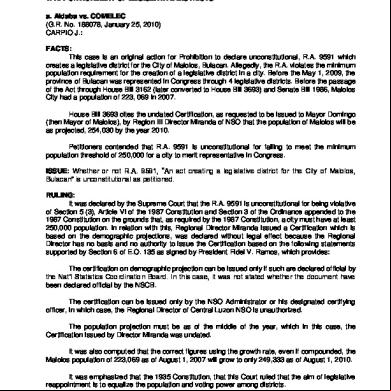

VII. LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT 1. APPORTIONMENT OF LEGISLATIVE DISTRICTS a. Aldaba vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 188078, January 25, 2010) CARPIO J.: FACTS: This case is an original action for Prohibition to declare unconstitutional, R.A. 9591 which creates a legislative district for the City of Malolos, Bulacan. Allegedly, the R.A. violates the minimum population requirement for the creation of a legislative district in a city. Before the May 1, 2009, the province of Bulacan was represented in Congress through 4 legislative districts. Before the age of the Act through House Bill 3162 (later converted to House Bill 3693) and Senate Bill 1986, Malolos City had a population of 223, 069 in 2007. House Bill 3693 cites the undated Certification, as requested to be issued to Mayor Domingo (then Mayor of Malolos), by Region III Director Miranda of NSO that the population of Malolos will be as projected, 254,030 by the year 2010. Petitioners contended that R.A. 9591 is unconstitutional for failing to meet the minimum population threshold of 250,000 for a city to merit representative in Congress. ISSUE: Whether or not R.A. 9591, “An act creating a legislative district for the City of Malolos, Bulacan” is unconstitutional as petitioned. RULING: It was declared by the Supreme Court that the R.A. 9591 is unconstitutional for being violative of Section 5 (3), Article VI of the 1987 Constitution and Section 3 of the Ordinance appended to the 1987 Constitution on the grounds that, as required by the 1987 Constitution, a city must have at least 250,000 population. In relation with this, Regional Director Miranda issued a Certification which is based on the demographic projections, was declared without legal effect because the Regional Director has no basis and no authority to issue the Certification based on the following statements ed by Section 6 of E.O. 135 as signed by President Fidel V. Ramos, which provides: The certification on demographic projection can be issued only if such are declared official by the Nat’l Statistics Coordination Board. In this case, it was not stated whether the document have been declared official by the NSCB. The certification can be issued only by the NSO or his designated certifying officer, in which case, the Regional Director of Central Luzon NSO is unauthorized. The population projection must be as of the middle of the year, which in this case, the Certification issued by Director Miranda was undated. It was also computed that the correct figures using the growth rate, even if compounded, the Malolos population of 223,069 as of August 1, 2007 will grow to only 249,333 as of August 1, 2010. It was emphasized that the 1935 Constitution, that this Court ruled that the aim of legislative reappointment is to equalize the population and voting power among districts.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 b. Aquino III v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 189793 April 7, 2010) Perez, J. FACTS: Republic Act No. 9176 created an additional legislative district for the province of Camarines Sur by reconfiguring the existing first and second legislative districts of the province. The said law originated from House Bill No. 4264 and was signed into law by President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo on 12 October 2009. To that effect, the first and second districts of Camarines Sur were reconfigured in order to create an additional legislative district for the province. Hence, the first district municipalities of Libmanan, Minalabac, Pamplona, Pasacao, and San Fernando were combined with the second district Municipalities of Milaor and Gainza to form a new second legislative district. Petitioners claim that the reapportionment introduced by Republic Act No. 9716 violates the constitutional standards that requires a minimum population of two hundred fifty thousand ( 250,000) for the creation of a legislative district. Thus, the proposed first district will end up with a population of less than 250,000 or only 176,383. ISSUE: Whether a population of 250,000 is an indispensable constitutional requirement for the creation of a new legislative district in a province. RULING: NO. The second sentence of Section 5 (3), Article VI of the constitution states that: “ Each city with a population of at least two hundred fifty thousand, or each province, shall have at least one representative.” There is a plain and clear distinction between the entitlement of a city to a district on one hand, and the entitlement of a province to a district on the other. For a province is entitled to at least a representative, there is nothing mentioned about the population. Meanwhile, a city must first meet a population minimum of 250,000 in order to be similarly entitled. It should be clearly read that Section 5(3) of the constitution requires a 250,000 minimum population only for a city to be entitled to a representative, but not so for a province.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 c. Mariano vs COMELEC (G.R. No 118577, March 7, 1995) Puno, J. FACTS: The petitioners assail the constitutionality of RA 7854 which is entitled “An Act Converting the Municipality of Makati into a Highly Urbanized City to be known as the City of Makati.” Suing as taxpayers, the first petition assails Sec. 2, 51 and 52 of RA 7854 as unconstitutional on the three grounds namely: 1) delineated the land area of the proposed City of Makati in violation of Art. X, Sec. 10 of the Constitution, in relation to Sec. 7 and 450 of LGC wherein area of local government unit should be made by metes and bounds with technical descriptions (Sec. 2); 2) attempts to alter or restart the “3 consecutive term” limit for local elective officials since the city shall acquire a new corporate existence is in violation of Art. X, Sec. 8 and Art. VI, Sec. 7 of the Constitution (Sec. 51); and 3a) reapportionment cannot be made by a special law; 3b) the addition of a legislative district was not expressed in the title of the bill; and 3c) Makati’s population, as per 1990 census, stands only at 450,000 (Sec. 52). ISSUE: Whether or not RA 7854 is unconstitutional. RULING: Yes, petition is dismissed for lack of merit in petitions. Sec. 2 did not add, subtract, divide or multiply the established land area of Makati. It was expressly stated that the city’s land area “shall comprise the present territory of the municipality.” Furthermore, the legitimate reason why the land area was not defined by metes and bounds with technical descriptions was because of the territorial dispute between the municipalities of Makati and Taguig over Fort Bonifacio. Out of respect, they did not want to foreclose the dispute by making a legislative finding of fact which could decide the issue. Petitioners have far complied with the requirements in challenging the constitutionality of a law. They merely pose a hypothetical issue which has yet to ripen to an actual case or controversy. Petitioners who are residents of Taguig (exception Mariano) are not also the proper parties to raise the issue. Also, they raised the issue in a petition for declaratory relief over which this Court has no jurisdiction. In Tobias v. Abalos ruling, it should be sufficient compliance if the title expresses the general subject and all the provisions are germane to such general subject. Makati has met the minimum population requirement. In fact, Section 3 of the Ordinance appended to the Constitution provides that a city whose population has increased to more than 250,000 shall be entitled to at least 1 congressional representative.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 d. Tobias vs Abalos (G.R. No. L-114783, December 8, 1994) BIDIN, J. FACTS: Complainants, invoking their right as taxpayers and as residents of Mandaluyong, filed a petition questioning the constitutionality of Republic Act No. 7675, otherwise known as "An Act Converting the Municipality of Mandaluyong into a Highly Urbanized City to be known as the City of Mandaluyong." Before the enactment of the law, Mandaluyong and San Juan belonged to the same legislative district. The petitioners contended that the act is unconstitutional for violation of three provisions of the constitution. First, it violates the one subject one bill rule. The bill provides for the conversion of Mandaluyong to HUC as well as the division of congressional district of San Juan and Mandaluyong into two separate district. Second, it also violate Section 5 of Article VI of the Constitution, which provides that the House of Representatives shall be composed of not more than two hundred and fifty , unless otherwise fixed by law. The division of San Juan and Mandaluyong into separate congressional districts increased the of the House of Representative beyond that provided by the Constitution. Third, Section 5 of Article VI also provides that within three years following the return of every census, the Congress shall make a reapportionment of legislative districts based on the standard provided in Section 5. Petitioners stated that the division was not made pursuant to any census showing that the minimum population requirement was attained. ISSUE: (1) Does RA 7675 violate the one subject one bill rule? (2) Does it violate Section 5(1) of Article VI of the Constitution on the limit of number of rep? (3) Is the inexistence of mention of census in the law show a lack of constitutional requirement? RULING: The Supreme Court ruled that the contentions are devoid of merit. With regards to the first contention of one subject one bill rule, the creation of a separate congressional district for Mandaluyong is not a separate and distinct subject from its conversion into a HUC but is a natural and logical consequence. In addition, a liberal construction of the "one title-one subject" rule has been invariably adopted by this court so as not to cripple or impede legislation. The second contention that the law violates the present limit of the number of representatives, the provision of the section itself show that the 250 limit is not absolute. The Constitution clearly provides that the House of Representatives shall be composed of not more than 250 , "unless otherwise provided by law”. Therefore, the increase in congressional representation mandated by R.A. No. 7675 is not unconstitutional. With regards, to the third contention that there is no mention in the assailed law of any census to show that Mandaluyong and San Juan had each attained the minimum requirement of 250,000 inhabitants to justify their separation into two legislative districts, unless otherwise proved that the requirements were not met, the said Act enjoys the presumption of having ed through the regular congressional processes, including due consideration by the of Congress of the minimum requirements for the establishment of separate legislative district The petition was dismissed for lack of merit.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 e. Montejo vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 118702, March 16, 1995) PUNO, J. FACTS: Petitioner Cerilo Roy Montejo, representative of the first district of Leyte, pleads for the annulment of Section 1 of Resolution no. 2736, redistricting certain municipalities in Leyte, on the ground that it violates the principle of equality of representation. The province of Leyte with the cities of Tacloban and Ormoc is composed of 5 districts. The 3rd district is composed of: Almeria, Biliran, Cabucgayan, Caibiran, Calubian, Culaba, Kawayan, Leyte, Maripipi, Naval, San Isidro, Tabango and Villaba. Biliran, located in the 3rd district of Leyte, was made its subprovince by virtue of Republic Act No. 2141 Section 1 enacted on 1959. Said section spelled out the municipalities comprising the subprovince: Almeria, Biliran, Cabucgayan, Caibiran, Culaba, Kawayan, Maripipi and Naval and all the territories comprised therein. On 1992, the Local Government Code took effect and the subprovince of Biliran became a regular province. (The conversion of Biliran into a regular province was approved by a majority of the votes cast in a plebiscite.) As a consequence of the conversion, eight municipalities of the 3rd district composed the new province of Biliran. A further consequence was to reduce the 3rd district to five municipalities (underlined above) with a total population of 146,067 as per the 1990 census. To remedy the resulting inequality in the distribution of inhabitants, voters and municipalities in the province of Leyte, respondent COMELEC held consultation meetings with the incumbent representatives of the province and other interested parties and on December 29, 1994, it promulgated the assailed resolution where, among others, it transferred the municipality of Capoocan of the 2nd district and the municipality of Palompon of the 4th district to the 3rd district of Leyte. ISSUE: Whether the unprecedented exercise by the COMELEC of the legislative power of redistricting and reapportionment is valid or not. RULING: No. Respondent COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack of jurisdiction when it promulgated Section 1 of its Resolution No. 2736 transferring the municipality of Capoocan of the Second District and the municipality of Palompon of the Fourth District to the Third District of Leyte. While concededly the conversion of Biliran into a regular province brought about an imbalance in the distribution of voters and inhabitants in the 5 districts of Leyte, the issue involves reapportionment of legislative districts, and petitioner’s remedy lies with Congress. This Court cannot itself make the reapportionment as petitioner would want. Also, respondent COMELEC relied on the ordinance appended to the 1987 constitution as the source of its power of redistricting which is traditionally regarded as part of the power to make laws. Said ordinance states that “The Commission on Elections is hereby empowered to make minor adjustments to the reapportionment herein made.” However, Minor adjustments does not involve change in the allocations per district. Examples include error in the correct name of a particular municipality or when a municipality in between which is still in the territory of one assigned district is forgotten. And consistent with the limits of its power to

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 make minor adjustments, section 3 of the Ordinance did not also give the respondent COMELEC any authority to transfer municipalities from one legislative district to another district. The power granted by section 3 to the respondent is to adjust the number of (not municipalities.)

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 f. Sema vs Commission on Elections (G.R. No. 177597, July 16, 2008) Carpio, J. FACTS: The Province of Maguindanao is part of ARMM. Cotabato City is part of the province of Maguindanao but it is not part of ARMM because Cotabato City voted against its inclusion in a plebiscite held in 1989. Maguindanao has two legislative districts. The 1st legislative district comprises of Cotabato City and 8 other municipalities. A law (RA 9054) was ed amending ARMM’s Organic Act and vesting it with power to create provinces, municipalities, cities and barangays. Pursuant to this law, the ARMM Regional Assembly created Shariff Kabunsuan (Muslim Mindanao Autonomy Act 201) which comprised of the municipalities of the 1st district of Maguindanao with the exception of Cotabato City. For the purposes of the 2007 elections, COMELEC initially stated that the 1st district is now only made of Cotabato City (because of MMA 201). But it later amended this stating that status quo should be retained; however, just for the purposes of the elections, the first district should be called Shariff Kabunsuan with Cotabato City – this is also while awaiting a decisive declaration from Congress as to Cotabato’s status as a legislative district (or part of any). Bai Sandra Sema was a congressional candidate for the legislative district of S. Kabunsuan with Cotabato (1st district). Later, Sema was contending that Cotabato City should be a separate legislative district and that votes therefrom should be excluded in the voting (probably because her rival Dilangalen was from there and D was winning – in fact he won). She contended that under the Constitution, upon creation of a province (S. Kabunsuan), that province automatically gains legislative representation and since S. Kabunsuan excludes Cotabato City – so in effect Cotabato is being deprived of a representative in the HOR. COMELEC maintained that the legislative district is still there and that regardless of S. Kabunsuan being created, the legislative district is not affected and so is its representation. ISSUE: Whether or not RA 9054 is unconstitutional. Whether or not ARMM can create validly LGUs. RULING: No. Congress cannot validly delegate to the ARMM Regional Assembly the power to create legislative districts, nothing in Sec. 20, Article X of the Constitution, authorizes autonomous regions, expressly or impliedly, to create or reapportion legislative districts. Accordingly, Sec. 19, Art. VI of R.A. 9054, granting the ARMM Regional Assembly the power to create provinces and cities, is void for being contrary to Sec. 5, Art. VI, and Sec. 20, Art. X, as well as Sec. 3 of the Ordinance appended to the Constitution. The power to create provinces, cities, municipalities and barangays was delegated by Congress to the ARMM Regional Assembly under Section 19, Article VI of RA 9054. However, pursuant to the Constitution, the power to create a province is with Congress and may not be validly delegated. Section 19 is, therefore, unconstitutional. MMA Act 201, enacted by the ARMM Regional Assembly and creating the Province of Shariff Kabunsuan, is void. The creation of Shariff Kabunsuan is invalid. Section 5 (1), Article VI of the Constitution vests in Congress the power to increase, through a law, the allowable hip in the House of Representatives. Section 5 (4) empowers Congress to reapportion legislative districts. The power to reapportion legislative districts necessarily includes the power to create legislative districts out of existing ones. Congress exercises these powers through

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 a law that Congress itself enacts, and not through a law that regional or local legislative bodies enact. The allowable hip of the House of Representatives can be increased, and new legislative districts of Congress can be created, only through a national law ed by Congress. It would be anomalous for regional or local legislative bodies to create or reapportion legislative districts for a national legislature like Congress. An inferior legislative body, created by a superior legislative body, cannot change the hip of the superior legislative body. "The Regional Assembly may exercise legislative power… except on the following matters: (k) National elections…”. Since the ARMM Regional Assembly has no legislative power to enact laws relating to national elections, it cannot create a legislative district whose representative is elected in national elections. Whenever Congress enacts a law creating a legislative district, the first representative is always elected in the "next national elections" from the effectivity of the law. Indeed, the office of a legislative district representative to Congress is a national office, and its occupant, a Member of the House of Representatives, is a national official. It would be incongruous for a regional legislative body like the ARMM Regional Assembly to create a national office when its legislative powers extend only to its regional territory. The office of a district representative is maintained by national funds and the salary of its occupant is paid out of national funds. It is a selfevident inherent limitation on the legislative powers of every local or regional legislative body that it can only create local or regional offices, respectively, and it can never create a national office. To allow the ARMM Regional Assembly to create a national office is to allow its legislative powers to operate outside the ARMM's territorial jurisdiction. This violates Section 20, Article X of the Constitution which expressly limits the coverage of the Regional Assembly's legislative powers "[w]ithin its territorial jurisdiction…”

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 2. QUALIFICATIONS a. Marcos vs COMELEC (G.R. No. 119976, September 18, 1995) KAPUNAN, J. FACTS: Imelda, a little over 8 years old, in or about 1938, established her domicile in Tacloban, Leyte where she studied and graduated high school in the Holy Infant Academy from 1938 to 1949. She then pursued her college degree, education, in St. Paul’s College now Divine Word University also in Tacloban. Subsequently, she taught in Leyte Chinese School still in Tacloban. She went to manila during 1952 to work with her cousin, the late speaker Daniel Romualdez in his office in the House of Representatives. In 1954, she married late President Ferdinand Marcos when he was still a Congressman of Ilocos Norte and was ed there as a voter. When Pres. Marcos was elected as Senator in 1959, they lived together in San Juan, Rizal where she ed as a voter. In 1965, when Marcos won presidency, they lived in Malacanang Palace and ed as a voter in San Miguel Manila. She served as member of the Batasang Pambansa and Governor of Metro Manila during 1978. Imelda Romualdez-Marcos was running for the position of Representative of the First District of Leyte for the 1995 Elections. Cirilo Roy Montejo, the incumbent Representative of the First District of Leyte and also a candidate for the same position, filed a “Petition for Cancellation and Disqualification" with the Commission on Elections alleging that petitioner did not meet the constitutional requirement for residency. The petitioner, in an honest misrepresentation, wrote seven months under residency, which she sought to rectify by adding the words "since childhood" in her Amended/Corrected Certificate of Candidacy filed on March 29, 1995 and that "she has always maintained Tacloban City as her domicile or residence. She arrived at the seven months residency due to the fact that she became a resident of the Municipality of Tolosa in said months. ISSUE: Whether petitioner has satisfied the 1 year residency requirement to be eligible in running as representative of the First District of Leyte. RULING: Residence is used synonymously with domicile for election purposes. The court are in favor of a conclusion ing petitioner’s claim of legal residence or domicile in the First District of Leyte despite her own declaration of 7 months residency in the district for the following reasons: 1. A minor follows domicile of her parents. Tacloban became Imelda’s domicile of origin by operation of law when her father brought them to Leyte; 2. Domicile of origin is only lost when there is actual removal or change of domicile, a bona fide intention of abandoning the former residence and establishing a new one, and acts which correspond with the purpose. In the absence and concurrence of all these, domicile of origin should be deemed to continue. 3. A wife does not automatically gain the husband’s domicile because the term “residence” in Civil Law does not mean the same thing in Political Law. When Imelda married late President Marcos in 1954, she kept her domicile of origin and merely gained a new home and not domicilium necessarium. 4. Assuming that Imelda gained a new domicile after her marriage and acquired right to choose a new one only after the death of Pres. Marcos, her actions upon returning to the

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 country clearly indicated that she chose Tacloban, her domicile of origin, as her domicile of choice. To add, petitioner even obtained her residence certificate in 1992 in Tacloban, Leyte while living in her brother’s house, an act, which s the domiciliary intention clearly manifested. She even kept close ties by establishing residences in Tacloban, celebrating her birthdays and other important milestones. WHEREFORE, having determined that petitioner possesses the necessary residence qualifications to run for a seat in the House of Representatives in the First District of Leyte, the COMELEC's questioned Resolutions dated April 24, May 7, May 11, and May 25, 1995 are hereby SET ASIDE. Respondent COMELEC is hereby directed to order the Provincial Board of Canvassers to proclaim petitioner as the duly elected Representative of the First District of Leyte.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 b. AQUINO vs. COMELEC (G.R. No. 120265, September 18, 1995) KAPUNAN, J. FACTS: On 20 March 1995, Agapito A. Aquino filed his Certificate of Candidacy for the position of Representative for the new Second Legislative District of Makati City. In his certificate of candidacy, Aquino stated that he was a resident of the aforementioned district for 10 months. Faced with a petition for disqualification, he amended the entry on his residency in his certificate of candidacy to 1 year and 13 days. The Commission on Elections dismissed the petition on 6 May and allowed Aquino to run in the election of 8 May. Aquino won. Acting on a motion for reconsideration of the above dismissal, the Commission on Election later issued an order suspending the proclamation of Aquino until the Commission resolved the issue. On 2 June, the Commission on Elections found Aquino ineligible and disqualified for the elective office for lack of constitutional qualification of residence. ISSUE: Whether “residency” in the certificate of candidacy actually connotes “domicile” to warrant the disqualification of Aquino from the position in the electoral district. RULING: No. The place “where a party actually or constructively has his permanent home,” where he, no matter where he may be found at any given time, eventually intends to return and remain, i.e., his domicile, is that to which the Constitution refers when it speaks of residence for the purposes of election law. The purpose is to exclude strangers or newcomers unfamiliar with the conditions and needs of the community from taking advantage of favorable circumstances existing in that community for electoral gain. Aquino’s certificate of candidacy in a previous (1992) election indicates that he was a resident and a ed voter of San Jose, Concepcion, Tarlac for more than 52 years prior to that election. Aquino’s connection to the Second District of Makati City is an alleged lease agreement of a condominium unit in the area. The intention not to establish a permanent home in Makati City is evident in his leasing a condominium unit instead of buying one. The short length of time he claims to be a resident of Makati (and the fact of his stated domicile in Tarlac and his claims of other residences in Metro Manila) indicate that his sole purpose in transferring his physical residence is not to acquire a new, residence or domicile but only to qualify as a candidate for Representative of the Second District of Makati City. Aquino was thus rightfully disqualified by the Commission on Elections.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 c. Coquilla vs COMELEC (G.R. No. 151914, July 31, 2002) MENDOZA, J. FACTS: Coquilla was born on 1938 of Filipino parents in Oras, Eastern Samar. He grew up and resided there until 1965, when he was subsequently naturalized as a U.S. citizen after ing the US Navy. In 1998, he came to the Philippines and took out a residence certificate, although he continued making several trips to the United States. Coquilla eventually applied for repatriation under R.A. No. 8171 which was approved. On November 10, 2000, he took his oath as a citizen of the Philippines. On November 21, 2000, he applied for registration as a voter of Butunga, Oras, Eastern Samar which was approved in 2001. On February 27, 2001, he filed his certificate of candidacy stating that he had been a resident of Oras, Eastern Samar for 2 years. Incumbent mayor Alvarez, who was running for re-election sought to cancel Coquilla’s certificate of candidacy on the ground that his statement as to the two year residency in Oras was a material misrepresentation as he only resided therein for 6 months after his oath as a citizen. Before the COMELEC could render a decision, elections commenced and Coquilla was proclaimed the winner. On July 19, 2001, COMELEC granted Alvarez’ petition and ordered the cancellation of petitioner’s certificate of candidacy. ISSUE: Whether or not Coquilla had been a resident of Oras, Eastern Samar at least one year before the elections held on May 14, 2001 as what he represented in his COC. RULING: No. The petitioner had not been a resident of Oras, Eastern Samar, for at least one year prior to the May 14, 2001 elections. Although Oras was his domicile of origin, petitioner lost the same when he became a US citizen after enlisting in the US Navy. From then on, until November 10, 2000, when he reacquired Philippine citizenship through repatriation, petitioner was an alien without any right to reside in the Philippines. In Caasi v. Comelec, infra., it was held that immigration to the US by virtue of the acquisition of a “green card” constitutes abandonment of domicile in the Philippines. The term "residence" is to be understood not in its common acceptation as referring to "dwelling" of "habitation," but rather to "domicile" or legal residence, that is "the place where a party actually or constructively has his permanent home, where he, no matter where he may be found at any given time, eventually intends to return and remain. A domicile of origin is acquired by every person at birth. It is usually the place where the child's parents reside and continues until the same is abandoned by acquisition of a new domicile.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 3. PARTY-LIST SYSTEM (REPUBLIC ACT NO. 7941) a. Atong Paglaum v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 203766 : April 2, 2013) CARPIO, J. FACTS: 52 party-list groups and organizations filed separate petitions totaling 54 with the Supreme Court (SC) in an effort to reverse various resolutions by the Commission on Elections (Comelec) disqualifying them from the May 2013 party-list race. The Comelec, in its assailed resolutions issued in October, November and December of 2012, ruled, among others, that these party-list groups and organizations failed to represent a marginalized and underrepresented sector, their nominees do not come from a marginalized and underrepresented sector, and/or some of the organizations or groups are not truly representative of the sector they intend to represent in Congress. Petitioners argued that the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion amounting to lack or excess of jurisdiction in disqualifying petitioners from participating in the 13 May 2013 party-list elections, either by denial of their new petitions for registration under the party-list system, or by cancellation of their existing registration and accreditation as party-list organizations; andsecond, whether the criteria for participating in the party-list system laid down inAng Bagong Bayani and Barangay Association for National Advancement and Transparency v. Commission on Elections(BANAT) should be applied by the COMELEC in the coming 13 May 2013 party-list elections. ISSUE: Whether or not the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion RULING: No. The COMELEC merely followed the guidelines set in the cases of Ang Bagong Bayani and BANAT. However, the Supreme Court remanded the cases back to the COMELEC as the Supreme Court now provides for new guidelines which abandoned some principles established in the two aforestated cases. Political Law- Party-list system Commissioner Christian S. Monsod, the main sponsor of the party-list system, stressed that "the party-list system is not synonymous with that of the sectoral representation." Indisputably, the framers of the 1987 Constitution intended the party-list system to include not only sectoral parties but also non-sectoral parties. The framers intended the sectoral parties to constitute a part, but not the entirety, of the party-list system. As explained by Commissioner Wilfredo Villacorta, political parties can participate in the party-list system "For as long as they field candidates who come from the different marginalized sectors that we shall designate in this Constitution." Republic Act No. 7941 or the Party-List System Act is the law that implements the party-list system prescribed in the Constitution. Section 3(a) of R.A. No. 7941 defines a "party" as "either a political party or a sectoral party or a coalition of parties." Clearly, a political party is different from a sectoral party. Section 3(c) of R.A. No. 7941 further provides that a "political party refers to an organized group of citizens advocating an ideology or platform, principles and policies for the general conduct of government. "On the other hand, Section 3(d) of R.A. No. 7941 provides that a "sectoral party refers to an organized group of citizens belonging to any of the sectors enumerated in Section 5 hereof whose principal advocacy pertains to the special interest and concerns of their sector. "R.A. No. 7941 provides different

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 definitions for a political and a sectoral party. Obviously, they are separate and distinct from each other. Under the party-list system, an ideology-based or cause-oriented political party is clearly different from a sectoral party. A political party need not be organized as a sectoral party and need not represent any particular sector. There is no requirement in R.A. No. 7941 that a national or regional political party must represent a "marginalized and underrepresented" sector. It is sufficient that the political party consists of citizens who advocate the same ideology or platform, or the same governance principles and policies, regardless of their economic status as citizens. Political Law- parameters in qualifying party- lists The COMELEC excluded from participating in the 13 May 2013 party-list elections those that did not satisfy these two criteria: (1) all national, regional, and sectoral groups or organizations must represent the "marginalized and underrepresented" sectors, and (2) all nominees must belong to the "marginalized and underrepresented" sector they represent. Petitioners may have been disqualified by the COMELEC because as political or regional parties they are not organized along sectoral lines and do not represent the "marginalized and underrepresented." Also, petitioners' nominees who do not belong to the sectors they represent may have been disqualified, although they may have a track record of advocacy for their sectors. Likewise, nominees of non-sectoral parties may have been disqualified because they do not belong to any sector. Moreover, a party may have been disqualified because one or more of its nominees failed to qualify, even if the party has at least one remaining qualified nominee. In determining who may participate in the coming 13 May 2013 and subsequent party-list elections, the COMELEC shall adhere to the following parameters: 1. Three different groups may participate in the party-list system: (1) national parties or organizations, (2) regional parties or organizations, and (3) sectoral parties or organizations. 2. National parties or organizations and regional parties or organizations do not need to organize along sectoral lines and do not need to represent any "marginalized and underrepresented" sector. 3. Political parties can participate in party-list elections provided they under the partylist system and do not field candidates in legislative district elections. A political party, whether major or not, that fields candidates in legislative district elections can participate in party-list elections only through its sectoral wing that can separately under the party-list system. The sectoral wing is by itself an independent sectoral party, and is linked to a political party through a coalition. 4. Sectoral parties or organizations may either be "marginalized and underrepresented" or lacking in "well-defined political constituencies." It is enough that their principal advocacy pertains to the special interest and concerns of their sector. The sectors that are "marginalized and underrepresented" include labor, peasant, fisherfolk, urban poor, indigenous cultural communities, handicapped, veterans, and overseas workers. The sectors that lack "welldefined political constituencies" include professionals, the elderly, women, and the youth. 5. A majority of the of sectoral parties or organizations that represent the "marginalized and underrepresented" must belong to the "marginalized and underrepresented" sector they represent. Similarly, a majority of the of sectoral

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 parties or organizations that lack "well-defined political constituencies" must belong to the sector they represent. The nominees of sectoral parties or organizations that represent the "marginalized and underrepresented," or that represent those who lack "well-defined political constituencies," either must belong to their respective sectors, or must have a track record of advocacy for their respective sectors. The nominees of national and regional parties or organizations must be bona-fide of such parties or organizations. 6. National, regional, and sectoral parties or organizations shall not be disqualified if some of their nominees are disqualified, provided that they have at least one nominee who remains qualified. This Court is sworn to uphold the 1987 Constitution, apply its provisions faithfully, and desist from engaging in socio-economic or political experimentations contrary to what the Constitution has ordained. Judicial power does not include the power to re-write the Constitution. Thus, the present petitions should be remanded to the COMELEC not because the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion in disqualifying petitioners, but because petitioners may now possibly qualify to participate in the coming 13 May 2013 party-list elections under the new parameters prescribed by this Court.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 b. Philippine Guardians Brotherhood, Inc. (PGBI) v. Commission on Elections (G.R. No. 190529, April 29, 2010) BRION, J. FACTS: Respondent delisted petitioner, a party list organization, from the roster of ed national, regional or sectoral parties, organizations or coalitions under the party-list system through its resolution, denying also the latter’s motion for reconsideration, in accordance with Section 6(8) of Republic Act No. 7941 (RA 7941), otherwise known as the Party-List System Act, which provides: Section 6. Removal and/or Cancellation of Registration. – The COMELEC may motu proprio or upon verified complaint of any interested party, remove or cancel, after due notice and hearing, the registration of any national, regional or sectoral party, organization or coalition on any of the following grounds: x x x x (8) It fails to participate in the last two (2) preceding elections or fails to obtain at least two per centum (2%) of the votes cast under the party-list system in the two (2) preceding elections for the constituency in which it has ed.[Emphasis supplied.] Petitioner was delisted because it failed to get 2% of the votes cast in 2004 and it did not participate in the 2007 elections. Petitioner filed its opposition to the resolution citing among others the misapplication in the ruling of MINERO v. COMELEC, but was denied for lack of merit. Petitioner elevated the matter to SC showing the excerpts from the records of Senate Bill No. 1913 before it became the law in question. ISSUES: WON COMELEC erred in delisting PGBI. RULINGS: Yes. Petition is granted. The law is clear that the COMELEC may motu proprio or upon verified complaint of any interested party, remove or cancel, after due notice and hearing, the registration of any national, regional or sectoral party, organization or coalition if it a) fails to participate in the last two (2) preceding elections; or b) fails to obtain at least two per centum (2%) of the votes cast under the party-list system in the two (2) preceding elections for the constituency in which it has ed. The word "or" is a disjunctive term signifying disassociation and independence of one thing from the other things enumerated; it should, as a rule, be construed in the sense in which it ordinarily implies, as a disjunctive word. Thus, the plain, clear and unmistakable language of the law provides for two (2) separate reasons for delisting. The disqualification for failure to garner 2% party-list votes in two preceding elections should now be understood, in light of the Banat ruling, to mean failure to qualify for a party-list seat in two preceding elections for the constituency in which it has ed. This, we declare, is how Section 6 (8) of RA 7941 should be understood and applied. We do so under our authority to state what the law is, and as an exception to the application of the principle of stare decisis. The MINERO ruling is an erroneous application of Section 6(8) of RA 7941; hence, it cannot sustain PGBI’s delisting from the roster of ed national, regional or sectoral parties, organizations or coalitions under the party-list system. First, the law is in the plain, clear and unmistakable language of the law which provides for two (2) separate reasons for delisting. Second, MINERO is diametrically opposed to the legislative intent of Section 6(8) of RA 7941, as PGBI’s cited congressional deliberations clearly show. MINERO therefore simply cannot stand.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 c. ANG LADLAD VS. COMELEC (G.R. No. 190582, April 8, 2010) DEL CASTILLO, J. FACTS: Petitioner is an organization composed of men and women who identify themselves as lesbians, gays, bisexuals, or trans-gendered individuals (LGBT’s). Incorporated in 2003, Ang Ladlad first applied for registration with the COMELEC in 2006 as a party-list organization under Republic Act 7941, otherwise known as the Party-List System Act. The application for accreditation was denied on the ground that the organization had no substantial hip base. In 2009, Ang Ladlad again filed a petition for registration with the COMELEC upon which it was dismissed on moral grounds. Ang Ladlad sought reconsideration but the COMELEC upheld its First Resolution, stating that “the party-list system is a tool for the realization of aspirations of marginalized individuals whose interests are also the nation’s. Until the time comes when Ladlad is able to justify that having mixed sexual orientations and transgender identities is beneficial to the nation, its application for accreditation under the party-list system will remain just that.” That “the Philippines cannot ignore its more than 500 years of Muslim and Christian upbringing, such that some moral precepts espoused by said religions have sipped into society and these are not publicly accepted moral norms.” COMELEC reiterated that petitioner does not have a concrete and genuine national political agenda to benefit the nation and that the petition was validly dismissed on moral grounds. It also argued for the first time that the LGBT sector is not among the sectors enumerated by the Constitution and RA 7941. Thus Ladlad filed this petition for Certiorari under Rule 65. ISSUE: Whether or not Petitioner should be accredited as a party-list organization under RA 7941. RULING: The Supreme Court granted the petition and set aside the resolutions of the COMELEC. It also directed the COMELEC to grant petitioner’s application for party-list accreditation. The enumeration of marginalized and under-represented sectors is not exclusive. The crucial element is not whether a sector is specifically enumerated, but whether a particular organization complies with the requirements of the Constitution and RA 7941. Ang Ladlad has sufficiently demonstrated its compliance with the legal requirements for accreditation. Nowhere in the records has the respondent ever found/ruled that Ang Ladlad is not qualified to as a party-list organization under any of the requisites under RA 7941. Our Constitution provides in Article III, Section 5 that “no law shall be made respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” At bottom, what our nonestablishment clause calls for is “government neutrality in religious matters. Clearly, “governmental reliance on religious justification is inconsistent with this policy of neutrality.” Laws of general application should apply with equal force to LGBTs and they deserve to participate in the party-list system on the same basis as other marginalized and under-represented sectors. The principle of non-discrimination requires the laws of general application relating to elections be applied to all persons, regardless of sexual orientation.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 d. ANAD v. COMELEC (GR No. 206987, September 10, 2013) PEREZ, J. FACTS: On November 7, 2012, the COMELEC en banc promulgated a resolution cancelling the Certificate of Registration and/or Accreditation of petitioner Alliance for Nationalism and Democracy (ANAD) on the following grounds: a) ANAD does not belong to, or come within the ambit of the marginalized and underrepresented sectors enumerated in Sec. 5 of RA 7941; b) The Certificate of Nomination submitted by the party only contained 3 nominees instead of 5, which is a failure to comply with the procedural requirement set forth in Sec. 4, Rule 3 of Resolution No. 9366; and c) ANAD failed to submit its statement of Contributions and Expenditures for the 2007 National and Local Elections as required by Sec. 14 of RA 7166 ANAD challenged the above-mentioned resolution. The Court remanded the case to the COMELEC for re-evaluation. In the assailed Resolution dated May 11, 2013, the COMELEC affirmed the cancellation of petitioner’s Certificate of Registration and/or Accreditation and disqualified them from participating in the 2013 Elections for violation of election laws and regulations. Hence, this petition ISSUE: WON the COMELEC gravely abused its discretion in promulgating the assailed Resolution without the benefit of a summary evidentiary hearing mandated by the due process clause. RULING: NO. ANAD was already given the opportunity to prove its qualifications during the summary hearing of August 23, 2012, during which ANAD submitted documents and other pieces of evidence to establish said qualifications. The COMELEC need not have called another summary hearing as they could readily resort to the documents and other piece of evidence previously submitted by petitioners in re-appraising ANAD’s qualifications. The COMELEC, being a specialized agency tasked with the supervision of elections all over the country, its factual findings, conclusions, rulings and decisions rendered on matters falling within its competence shall not be interfered with by this Court in the absence of grave abuse of discretion or any jurisdictional infirmity or error of law. As empowered by law, the COMELEC may cancel, after due notice and hearing, the registration of any party-list organization if it violates or fails to comply with laws, rules or regulations relating to elections Compliance with Section 8 of R.A. No. 7941 is essential as the said provision is a safeguard against arbitrariness. Section 8 of R.A. No. 7941 rids a party-list organization of the prerogative to substitute and replace its nominees, or even to switch the order of the nominees, after submission of the list to the COMELEC. The COMELEC will only determine whether the nominees all the requirements prescribed by the law and whether or not the nominees possess all the qualifications and none of the disqualifications. Thereafter, the names of the nominees will be published in newspapers of general circulation. Although the people vote for the party-list organization itself in a party-list system of election, not for the individual nominees, they still have the right to know who the nominees of any particular party-list organization are. The publication of the list of the party-list nominees in newspapers of general circulation serves that right of the people, enabling the voters to make intelligent and informed choice.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 e. Abang Lingkod Party-list vs COMELEC (G.R. No. 206952, October 22, 2013) REYES, J. FACTS: Abang Lingkod Party-list is a sectoral organization that represents the interest of peasant farmers and fisherfolk. On May 31, 2012, the party manifested its intent to participate in the May 2013 elections. The COMELEC issued Resolution No. 9513 which required previously ed party-list groups that have filed their respective Manifestations of Intent to undergo summary evidentiary hearing for purposes of determining their continuing compliance with the requirements under RA 7941. The party complied with the needed documents and after due proceedings, the COMELEC en banc cancelled their registration as a party-list group. They pointed out that Abang Lingkod (1) failed to establish its track record in uplifting the cause of the marginalized and underrepresented; (2) it merely offered photographs of some alleged activities it conducted after the May 2010 elections; and (3) failed to show that nominees are themselves marginalized and underrepresented or that they have been involved in activities aimed at improving the plight of the sectors it claims to represent. Abang Lingkod then filed a petition alleging COMELEC gravely abused its discretion in cancelling its registration under the party-list system. This was consolidated with 51 other separate petitions whose registration were cancelled or who were denied registration. On April 2, 2013, the Court laid down new parameters to be observed by the COMELEC in screening parties, organizations or associations seeking registration and/or accreditation under the party-list system. The Court then remanded to COMELEC the cases of previously ed partylist groups, including that of Abang Lingkod, to determine whether they are qualified pursuant to the new parameters and, in the affirmative, be allowed to participate in the May 2013 party-list elections. On May 10, 2013, the COMELEC issued a Resolution affirming the cancellation of Abang Lingkod’s registration. The party sought for reconsideration, however, withdrew it and filed instead this petition, claiming that the former gravely abused its discretion when it affirmed the cancellation of its registration when it should have allowed it to present evidence to prove its qualification as a party-list group pursuant to the Atong Paglaum ruling. On the other hand, the COMELEC asserts that the petition should be dismissed for lack of merit. ISSUE: WON COMELEC gravely abused its discretion in canceling the party’s registration under the party-list system. RULING: YES. The COMELEC gravely abused its discretion when it insisted on requiring ABANG LINGKOD to prove its track record notwithstanding that a group's track record is no longer required pursuant to the Court's pronouncement in Atong Paglaum. Abang Lingkod's registration must be cancelled due to its misrepresentation is a conclusion derived from a simplistic reading of the provisions of R.A. No. 7941 and the import of the Court's disposition in Atong Paglaum. Not every misrepresentation committed by national, regional, and sectoral groups or organizations would merit the denial or cancellation of their registration under the party-list system. The misrepresentation must relate to their qualification as a party-list group. Under Section 5 of R.A. No. 7941, groups intending to under the party-list system are not required to submit evidence of their track record; they are merely required to attach to their verified petitions their "constitution, by-laws, platform of government, list of officers, coalition agreement, and other relevant information as may be required by the COMELEC."

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 Sectoral parties or organizations are no longer required to adduce evidence showing their track record, i.e., proof of activities that they have undertaken to further the cause of the sector they represent. Indeed, it is enough that their principal advocacy pertains to the special interest and concerns of their sector. Otherwise stated, it is sufficient that the ideals represented by the sectoral organizations are geared towards the cause of the sector/s, which they represent. If at all, evidence showing a track record in representing the marginalized and underrepresented sectors is only required from nominees of sectoral parties or organizations that represent the marginalized and underrepresented who do not factually belong to the sector represented by their party or organization. Also, a declaration of an untruthful statement in a petition for registration under Section 6 (6) of R.A. No. 7941, in order to be a ground for the refusal and/or cancellation of registration under the party-list system, must pertain to the qualification of the party, organization or coalition under the party-list system. In order to justify the cancellation or refusal of registration of a group, there must be a deliberate attempt to mislead, misinform, or hide a fact, which would otherwise render the group disqualified from participating in the party-list elections. There was no necessity for the COMELEC to conduct further summary evidentiary hearing to assess the qualification of Abang Lingkod pursuant to Atong Paglaum. It was only remanded to the them so that they may reassess, based on the evidence already submitted, whether the party qualifies to participate in the party-list system. The records also disclose that Abang Lingkod was able to file with the COMELEC a motion for reconsideration of the Resolution dated May 10, 2013, negating its claim that it was denied due process. As it has been held, deprivation of due process cannot be successfully invoked where a party was given a chance to be heard on his motion for reconsideration.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 f. COCOFED v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 207026, August 6, 2013) BRION, J. FACTS: Petitioner COCOFED-Philippine Coconut Producers Federation Inc. is an organization and dectoral party whose hip comes from the peasant sector, particularly the coconut farmers and producers. On May 29, 2012, it manifested with the COMELEC its intent to participate in the party-list elections of May 13, 2013 and submitted only 2 nominees - Atty. Emerito Calderon and Atty. Domingo Espina. Pursuant to Res. No. 9513, the COMELEC conducted a summary hearing to determine whether COCOFED, among several party-list groups, had continuously complied with the legal requirements. In its November 7, 2012 resolution, the COMELEC cancelled petitioner’s registration and accreditation as a partylist organization. On Dec. 4, the party submitted the names of Charles Avila in substitution of Atty. Espina and Efren Villaseñor as its third nominee. Pursuant to the Atong Paglaum ruling, the Court remanded all the petitions to the COMELEC to determine their compliance with the new parameters set by the Court in that case. On May 10, 2013, COMELEC issued its assailed resolution, maintaining its earlier ruling for the party’s failure to comply with the requirement of Sec. 8 of RA 7941 to submit a list of not less than 5 nominees. COCOFED moved for reconsideration only to withdraw its motion later and instead, filed a Manifestation with Urgent Request to it Additional Nominees with the COMELEC, namely: Felino Gutierrez and Rodolfo de Asis. On May 24, 2013, the COMELEC issued a resolution declaring the cancellation final and executory. COCOFED argues that the COMELEC gravely abused its discretion in issuing the assailed resolution on the following grounds: a) COMELEC violated its right to due process; b) Failure to submit the required number of nominees was based on the good faith belief that its submission was sufficient for purposes of the elections, that it could still be remedied, and the number of nominees becomes significant only when a party-list organization is able to attain a sufficient number of votes which would qualify it for a seat in the House of Representatives; and c)COMELEC violated its right to equal protection of the laws since at least 2 other party-list groups (ACT-CIS and MTM Phils.) which failed to submit 5 nominees were included in the official list of party-list groups. ISSUE: WON Comelec gravely abused its discretion on issuing assailed Resolution RULING: No. COCOFED’s failure to submit a list of 5 nominees, despite ample opportunity to do so before the elections, is a violation imputable to the party under Section 6 (5) of RA 7941. Under Section 6 (5) of RA No. 7941, violation of or failure to comply with laws, rules or regulations relating to elections is a ground for the cancellation of registration. However, not every kind of violation automatically warrants the cancellation of a party-list group's registration. Since a reading of the entire Section 6 shows that all the grounds for cancellation actually pertain to the party itself, then the laws, rules and regulations violated to warrant cancellation under Section 6 (5) must be one that is primarily imputable to the party itself and not one that is chiefly confined to an individual member or its nominee. The language of Sec. 8 of RA 7941 does not only use the word ‘shall’ in connection with the requirement of submitting a list of nominees; it uses this mandatory term in conjunction with the number of names to be submitted that is couched negatively, i.e., “not less than five.”

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 While COCOFED’s failure to submit a complete list of requirements may not have been among the grounds cited by the COMELEC in earlier cancelling its registration, this is not sufficient to a finding of grave abuse of discretion. The fact that a party-list group is entitled to no more than three seats in Congress, regardless of the number of votes it may garner, 24 does not render Section 8 of RA No. 7941 permissive in nature. The Court cannot discern any valid reason why a party-list group cannot comply with the statutory requirement. A party is not allowed to simply refuse to submit a list containing "not less than five nominees" and consider the deficiency as a waiver on its part. A party may have been disqualified because one or more of its nominees fail to qualify, even if party has at least one remaining qualified nominee. The Court in no way authorized a party-list group's inexcusable failure, if not outright refusal, to comply with the clear letter of the law on the submission of at least five nominees.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 g. AMORES v HRET (G.R. No. 189600, June 29, 2010) CARPIO MORALES, J. FACTS: Petition for certiorari challenging the assumption of office of one Emmanuel Joel Villanueva as representative of CIBAC in the HoR. Petitioner argues that Villanueva was 31 at the time of filing of nomination, beyond the age limit of 30 which was the limit imposed by RA 7941 for "youth sector" and his change of affiliation from Youth Sector to OFW and families not affected six months prior to elections. ISSUE: Whether the requirement for youth sector representatives apply to respondent Villanueva RULING: The law is clear that representative of youth sector should be between 25 to 30 and sectoral representation should be changed 6 months prior to elections. Villanueva is ineligible to hold office as a member of HoR representing CIBAC because he violated both requirements. Qualifications for public office are continuing requirements and must be possessed not only at the time of appointment or election or assumption of office but during the officer's entire tenure. Once any of the required qualifications is lost, his title may be seasonably challenged.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 h. Bantay Republic Act. v. COMELEC (G.R. No. 177271, May 4, 2007) GARCIA, J. FACTS: Before the Court are two consolidated petitions for certiorari and mandamus to nullify and set aside certain issuances of the Commission on Elections (Comelec) respecting party-list groups which have manifested their intention to participate in the party-list elections on May 14, 2007. A number of organized groups filed the necessary manifestations and subsequently were accredited by the Comelec to participate in the 2007 elections. Bantay Republic Act (BA-RA 7941) and the Urban Poor for Legal Reforms (UP-LR) filed with the Comelec an Urgent Petition seeking to disqualify the nominees of certain party-list organizations. Meanwhile petitioner Rosales, in G.R. No. 177314, addressed 2 letters to the Director of the Comelec’s Law Department requesting a list of that groups’ nominees. Evidently unbeknownst then to Ms. Rosales, et al., was the issuance of Comelec en banc Resolution 07-0724 under date April 3, 2007 virtually declaring the nominees’ names confidential and in net effect denying petitioner Rosales’ basic disclosure request. According to COMELEC, there is nothing in R.A. 7941 that requires the Comelec to disclose the names of nominees, and that party list elections must not be personality oriented according to Chairman Abalos. In the first petition (G.R. No. 177271), BA-RA 7941 and UP-LR assail the Comelec resolutions accrediting private respondents Biyaheng Pinoy et al., to participate in the forthcoming party-list elections without simultaneously determining whether or not their respective nominees possess the requisite qualifications defined in R.A. No. 7941, or the "Party-List System Act" and belong to the marginalized and underrepresented sector each seeks to. In the second petition (G.R. No. 177314), petitioners Loreta Ann P. Rosales, Kilosbayan Foundation and Bantay Katarungan Foundation impugn Comelec Resolution dated April 3, 2007. While both petitions commonly seek to compel the Comelec to disclose or publish the names of the nominees of the various party-list groups named in the petitions, BA-RA 7941 and UP-LR have the additional prayers that the 33 private respondents named therein be "declare[d] as unqualified to participate in the party-list elections and that the Comelec be ened from allowing respondent groups from participating in the elections. ISSUE: WON respondent Comelec, by refusing to reveal the names of the nominees of the various party-list groups, has violated the right to information and free access to documents as guaranteed by the Constitution. RULING: Yes. The Supreme Court ruled that the COMELEC committed grave abuse of discretion in refusing to release the names of said candidates based on the right to information. That the right to information is being sought after in the context of the electoral climate and the controversial PartyList system under Republic Act No. 7941 or the Party-List System Act highlights the uniqueness of these cases. The last sentence of Section 7 of R.A. 7941 reading: "[T]he names of the party-list nominees shall not be shown on the certified list" is certainly not a justifying card for the Comelec to deny the requested disclosure. To us, the prohibition imposed on the Comelec under said Section 7 is limited in scope and duration, meaning, that it extends only to the certified list which the same provision requires to be posted in the polling places on election day. To stretch the coverage of the prohibition

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 to the absolute is to read into the law something that is not intended. As it were, there is absolutely nothing in R.A. No. 7941 that prohibits the Comelec from disclosing or even publishing through mediums other than the "Certified List" the names of the party-list nominees. The Comelec obviously misread the limited non-disclosure aspect of the provision as an absolute bar to public disclosure before the May 2007 elections. The interpretation thus given by the Comelec virtually tacks an unconstitutional dimension on the last sentence of Section 7 of R.A. No. 7941 It has been repeatedly said in various contexts that the people have the right to elect their representatives on the basis of an informed judgment. Hence the need for voters to be informed about matters that have a bearing on their choice. The ideal cannot be achieved in a system of blind voting, as veritably advocated in the assailed resolution of the Comelec. The Court, since the 1914 case of Gardiner v. Romulo, 21 has consistently made it clear that it frowns upon any interpretation of the law or rules that would hinder in any way the free and intelligent casting of the votes in an election. 22 So it must be here for still other reasons articulated earlier. In all, we agree with the petitioners that respondent Comelec has a constitutional duty to disclose and release the names of the nominees of the party-list groups named in the herein petitions.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 i. BANAT v COMELEC (G.R. No. 179271, April 21, 2009) CARPIO, J. FACTS: In July and August 2007, the COMELEC, sitting as the National Board of Canvassers, made a partial proclamation of the winners in the party-list elections which was held in May 2007. In proclaiming the winners and apportioning their seats, the COMELEC considered the following rules: 1. In the lower house, 80% shall comprise the seats for legislative districts, while the remaining 20% shall come from party-list representatives (Sec. 5, Article VI, 1987 Constitution); 2. Pursuant to Sec. 11b of R.A. 7941 or the Party-List System Act, a party-list which garners at least 2% of the total votes cast in the party-list elections shall be entitled to one seat; 3. If a party-list garners at least 4%, then it is entitled to 2 seats; if it garners at least 6%, then it is entitled to 3 seats – this is pursuant to the 2-4-6 rule or the Panganiban Formula from the case of Veterans Federation Party vs COMELEC. 4. In no way shall a party be given more than three seats even if if garners more than 6% of the votes cast for the party-list election (3 seat cap rule, same case). The Barangay Association for National Advancement and Transparency (BANAT), a party-list candidate, questioned the proclamation as well as the formula being used. BANAT averred that the 2% threshold is invalid; Sec. 11 of RA 7941 is void because its provision that a party-list, to qualify for a congressional seat, must garner at least 2% of the votes cast in the party-list election, is not ed by the Constitution. Further, the 2% rule creates a mathematical impossibility to meet the 20% party-list seat prescribed by the Constitution. BANAT also questions if the 20% rule is a mere ceiling or is it mandatory. If it is mandatory, then with the 2% qualifying vote, there would be instances when it would be impossible to fill the prescribed 20% share of party-lists in the lower house. BANAT also proposes a new computation (which shall be discussed in the “HELD” portion of this digest). On the other hand, BAYAN MUNA, another party-list candidate, questions the validity of the 3 seat rule (Section 11a of RA 7941). It also raised the issue of whether or not major political parties are allowed to participate in the party-list elections or is the said elections limited to sectoral parties. ISSUES: I. How is the 80-20 rule observed in apportioning the seats in the lower house? II. Whether or not the 20% allocation for party-list representatives mandatory or a mere ceiling. III. Whether or not the 2% threshold to qualify for a seat valid. IV. How are party-list seats allocated? V. Whether or not major political parties are allowed to participate in the party-list elections. VI. Whether or not the 3 seat cap rule (3 Seat Limit Rule) is valid.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 RULING: I. The 80-20 rule is observed in the following manner: for every 5 seats allotted for legislative districts, there shall be one seat allotted for a party-list representative. Originally, the 1987 Constitution provides that there shall be not more than 250 of the lower house. Using the 80-20 rule, 200 of that will be from legislative districts, and 50 would be from party-list representatives. However, the Constitution also allowed Congress to fix the number of the hip of the lower house as in fact, it can create additional legislative districts as it may deem appropriate. As can be seen in the May 2007 elections, there were 220 district representatives, hence applying the 80-20 rule or the 5:1 ratio, there should be 55 seats allotted for party-list representatives. How did the Supreme Court arrive at 55? This is the formula: (Current Number of Legislative DistrictRepresentatives ÷ 0.80) x (0.20) = Number of Seats Available to Party-List Representatives Hence, (220 ÷ 0.80) x (0.20) = 55 II. The 20% allocation for party-list representatives is merely a ceiling – meaning, the number of partylist representatives shall not exceed 20% of the total number of the of the lower house. However, it is not mandatory that the 20% shall be filled. III. No. Section 11b of RA 7941 is unconstitutional. There is no constitutional basis to allow that only party-lists which garnered 2% of the votes cast are qualified for a seat and those which garnered less than 2% are disqualified. Further, the 2% threshold creates a mathematical impossibility to attain the ideal 80-20 apportionment. The Supreme Court explained: To illustrate: There are 55 available party-list seats. Suppose there are 50 million votes cast for the 100 participants in the party list elections. A party that has two percent of the votes cast, or one million votes, gets a guaranteed seat. Let us further assume that the first 50 parties all get one million votes. Only 50 parties get a seat despite the availability of 55 seats. Because of the operation of the two percent threshold, this situation will repeat itself even if we increase the available party-list seats to 60 seats and even if we increase the votes cast to 100 million. Thus, even if the maximum number of parties get two percent of the votes for every party, it is always impossible for the number of occupied party-list seats to exceed 50 seats as long as the two percent threshold is present. It is therefore clear that the two percent threshold presents an unwarranted obstacle to the full implementation of Section 5(2), Article VI of the Constitution and prevents the attainment of “the broadest possible representation of party, sectoral or group interests in the House of Representatives.” IV. Instead, the 2% rule should mean that if a party-list garners 2% of the votes cast, then it is guaranteed a seat, and not “qualified”. This allows those party-lists garnering less than 2% to also get a seat. But how? The Supreme Court laid down the following rules: 1. The parties, organizations, and coalitions shall be ranked from the highest to the lowest based on the number of votes they garnered during the elections.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 2. The parties, organizations, and coalitions receiving at least two percent (2%) of the total votes cast for the party-list system shall be entitled to one guaranteed seat each. 3. Those garnering sufficient number of votes, according to the ranking in paragraph 1, shall be entitled to additional seats in proportion to their total number of votes until all the additional seats are allocated. 4. Each party, organization, or coalition shall be entitled to not more than three (3) seats. In computing the additional seats, the guaranteed seats shall no longer be included because they have already been allocated, at one seat each, to every two-percenter. Thus, the remaining available seats for allocation as “additional seats” are the maximum seats reserved under the Party List System less the guaranteed seats. Fractional seats are disregarded in the absence of a provision in R.A. No. 7941 allowing for a rounding off of fractional seats. In short, there shall be two rounds in determining the allocation of the seats. In the first round, all party-lists which garnered at least 2% of the votes cast (called the two-percenters) are given their one seat each. The total number of seats given to these two-percenters are then deducted from the total available seats for party-lists. In this case, 17 party-lists were able to garner 2% each. There are a total 55 seats available for party-lists hence, 55 minus 17 = 38 remaining seats. (Please refer to the full text of the case for the tabulation). The number of remaining seats, in this case 38, shall be used in the second round, particularly, in determining, first, the additional seats for the two-percenters, and second, in determining seats for the party-lists that did not garner at least 2% of the votes cast, and in the process filling up the 20% allocation for party-list representatives. How is this done? Get the total percentage of votes garnered by the party and multiply it against the remaining number of seats. The product, which shall not be rounded off, will be the additional number of seats allotted for the party list – but the 3 seat limit rule shall still be observed. Example: In this case, the BUHAY party-list garnered the highest total vote of 1,169,234 which is 7.33% of the total votes cast for the party-list elections (15,950,900). Applying the formula above: (Percentage of vote garnered) x (remaining seats) = number of additional seat Hence, 7.33% x 38 = 2.79 Rounding off to the next higher number is not allowed so 2.79 remains 2. BUHAY is a twopercenter which means it has a guaranteed one seat PLUS additional 2 seats or a total of 3 seats. Now if it so happens that BUHAY got 20% of the votes cast, it will still get 3 seats because the 3 seat limit rule prohibits it from having more than 3 seats. Now after all the tw0-percenters were given their guaranteed and additional seats, and there are still unoccupied seats, those seats shall be distributed to the remaining party-lists and those higher in rank in the voting shall be prioritized until all the seats are occupied.

DIGESTED CASES IN CONSTITUTIONAL LAW 1| ATTY. ANTONIO EDUARDO NACHURA | 1B, 1H, 1N 2018-2019 V. No. By a vote of 8-7, the Supreme Court continued to disallow major political parties (the likes of UNIDO, LABAN, etc) from participating in the party-list elections. Although the ponencia (Justice Carpio) did point out that there is no prohibition either from the Constitution or from RA 7941 against major political parties from participating in the party-list elections as the word “party” was not qualified and that even the framers of the Constitution in their deliberations deliberately allowed major political parties to participate in the party-list elections provided that they establish a sectoral wing which represents the marginalized (indirect participation), Justice Puno, in his separate opinion, concurred by 7 other justices, explained that the will of the people defeats the will of the framers of the Constitution precisely because it is the people who ultimately ratified the Constitution – and the will of the people is that only the marginalized sections of the country shall participate in the party-list elections. Hence, major political parties cannot participate in the party-list elections, directly or indirectly. VI. Yes, the 3 seat limit rule is valid. This is one way to ensure that no one party shall dominate the party-list system.