Digests Ltd 2 621n1t

This document was ed by and they confirmed that they have the permission to share it. If you are author or own the copyright of this book, please report to us by using this report form. Report 3b7i

Overview 3e4r5l

& View Digests Ltd 2 as PDF for free.

More details w3441

- Words: 1,001

- Pages: 4

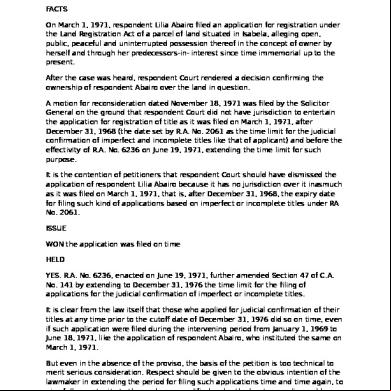

Director of Lands vs. Abairo, GR L-34602, May 31, 1979 FACTS On March 1, 1971, respondent Lilia Abairo filed an application for registration under the Land Registration Act of a parcel of land situated in Isabela, alleging open, public, peaceful and uninterrupted possession thereof in the concept of owner by herself and through her predecessors-in- interest since time immemorial up to the present. After the case was heard, respondent Court rendered a decision confirming the ownership of respondent Abairo over the land in question. A motion for reconsideration dated November 18, 1971 was filed by the Solicitor General on the ground that respondent Court did not have jurisdiction to entertain the application for registration of title as it was filed on March 1, 1971, after December 31, 1968 (the date set by R.A. No. 2061 as the time limit for the judicial confirmation of imperfect and incomplete titles like that of applicant) and before the effectivity of R.A. No. 6236 on June 19, 1971, extending the time limit for such purpose. It is the contention of petitioners that respondent Court should have dismissed the application of respondent Lilia Abairo because it has no jurisdiction over it inasmuch as it was filed on March 1, 1971, that is, after December 31, 1968, the expiry date for filing such kind of applications based on imperfect or incomplete titles under RA No. 2061. ISSUE WON the application was filed on time HELD YES. R.A. No. 6236, enacted on June 19, 1971, further amended Section 47 of C.A. No. 141 by extending to December 31, 1976 the time limit for the filing of applications for the judicial confirmation of imperfect or incomplete titles. It is clear from the law itself that those who applied for judicial confirmation of their titles at any time prior to the cutoff date of December 31, 1976 did so on time, even if such application were filed during the intervening period from January 1, 1969 to June 18, 1971, like the application of respondent Abairo, who instituted the same on March 1, 1971. But even in the absence of the proviso, the basis of the petition is too technical to merit serious consideration. Respect should be given to the obvious intention of the lawmaker in extending the period for filing such applications time and time again, to give full opportunity to those who are qualified under the law to own disposable

lands of the public domain and thus reduce the number of landless among the citizenry.

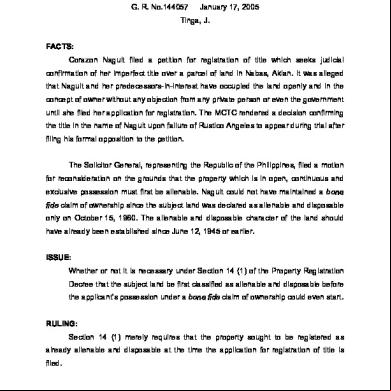

Republic vs CA, GR 108998, August 1994 FACT On June 17, 1978, respondent spouses bought two parcels of land as their residence. At the time of the purchase, respondent spouses where then natural-born Filipino citizens. On February 5, 1987, the spouses filed an application for registration of title of the two parcels of land before the RTC of San Pablo City. This time, however, they were no longer Filipino citizens and have opted to embrace Canadian citizenship through naturalization. An opposition was filed by the Republic and after the parties have presented their respective evidence, the court a quo rendered a decision confirming private respondents' title to the lots in question. Petitioner submits that private respondents have not acquired proprietary rights over the subject properties before they acquired Canadian citizenship to justify the registration thereof in their favor. It maintains that even privately owned uned lands are presumed to be public lands under the principle that lands of whatever classification belong to the State under the Regalian doctrine. Thus, before the issuance of the certificate of title, the occupant is not in the juridical sense the true owner of the land since it still pertains to the State. ISSUE 1. WON the respondents acquired proprietary rights over the subject properties to justify the registration thereof in their favor 2. WON a foreign national apply for registration of title over a parcel of land which he acquired by purchase while still a citizen of the Philippines, from a vendor who has complied with the requirements for registration under the Public Land Act? HELD 1. YES. The weight of authority is that open, exclusive and undisputed possession of alienable public land for the period prescribed by law creates the legal fiction whereby the land ceases to be public land and becomes private property. When the conditions set by law are complied with, the possessor of the land, by operation of law, acquires a right to a grant, a government grant, without the necessity of a certificate of title being issued. The Torrens system was not established as a means for the acquisition of title to private land. It merely confirms ownership. 2. YES. Private respondents were undoubtedly natural-born Filipino citizens at the time of the acquisition of the properties and by virtue thereof, acquired vested

rights thereon, tacking in the process, the possession in the concept of owner and the prescribed period of time held by their predecessors-in-interest under the Public Land Act. The Constitution itself allows private respondents to the contested parcels of land in their favor, to wit, “A natural-born citizen of the Philippines who has lost his Philippine citizenship may be a transferee of private lands, subject to limitations provided by law.” Pursuant thereto, BP 185 was ed into law, the relevant provision of which provides, “Any natural-born citizen of the Philippines who has lost his Philippine citizenship and who has the legal capacity to enter into a contract under Philippine laws may be a transferee of a private land up to a maximum area of one thousand square meters, in the case of urban land, or one hectare in the case of rural land, to be used by him as his residence…” Even if private respondents were already Canadian citizens at the time they applied for registration of the properties in question, said properties as discussed above were already private lands; consequently, there could be no legal impediment for the registration thereof by respondents in view of what the Constitution ordains.

lands of the public domain and thus reduce the number of landless among the citizenry.

Republic vs CA, GR 108998, August 1994 FACT On June 17, 1978, respondent spouses bought two parcels of land as their residence. At the time of the purchase, respondent spouses where then natural-born Filipino citizens. On February 5, 1987, the spouses filed an application for registration of title of the two parcels of land before the RTC of San Pablo City. This time, however, they were no longer Filipino citizens and have opted to embrace Canadian citizenship through naturalization. An opposition was filed by the Republic and after the parties have presented their respective evidence, the court a quo rendered a decision confirming private respondents' title to the lots in question. Petitioner submits that private respondents have not acquired proprietary rights over the subject properties before they acquired Canadian citizenship to justify the registration thereof in their favor. It maintains that even privately owned uned lands are presumed to be public lands under the principle that lands of whatever classification belong to the State under the Regalian doctrine. Thus, before the issuance of the certificate of title, the occupant is not in the juridical sense the true owner of the land since it still pertains to the State. ISSUE 1. WON the respondents acquired proprietary rights over the subject properties to justify the registration thereof in their favor 2. WON a foreign national apply for registration of title over a parcel of land which he acquired by purchase while still a citizen of the Philippines, from a vendor who has complied with the requirements for registration under the Public Land Act? HELD 1. YES. The weight of authority is that open, exclusive and undisputed possession of alienable public land for the period prescribed by law creates the legal fiction whereby the land ceases to be public land and becomes private property. When the conditions set by law are complied with, the possessor of the land, by operation of law, acquires a right to a grant, a government grant, without the necessity of a certificate of title being issued. The Torrens system was not established as a means for the acquisition of title to private land. It merely confirms ownership. 2. YES. Private respondents were undoubtedly natural-born Filipino citizens at the time of the acquisition of the properties and by virtue thereof, acquired vested

rights thereon, tacking in the process, the possession in the concept of owner and the prescribed period of time held by their predecessors-in-interest under the Public Land Act. The Constitution itself allows private respondents to the contested parcels of land in their favor, to wit, “A natural-born citizen of the Philippines who has lost his Philippine citizenship may be a transferee of private lands, subject to limitations provided by law.” Pursuant thereto, BP 185 was ed into law, the relevant provision of which provides, “Any natural-born citizen of the Philippines who has lost his Philippine citizenship and who has the legal capacity to enter into a contract under Philippine laws may be a transferee of a private land up to a maximum area of one thousand square meters, in the case of urban land, or one hectare in the case of rural land, to be used by him as his residence…” Even if private respondents were already Canadian citizens at the time they applied for registration of the properties in question, said properties as discussed above were already private lands; consequently, there could be no legal impediment for the registration thereof by respondents in view of what the Constitution ordains.